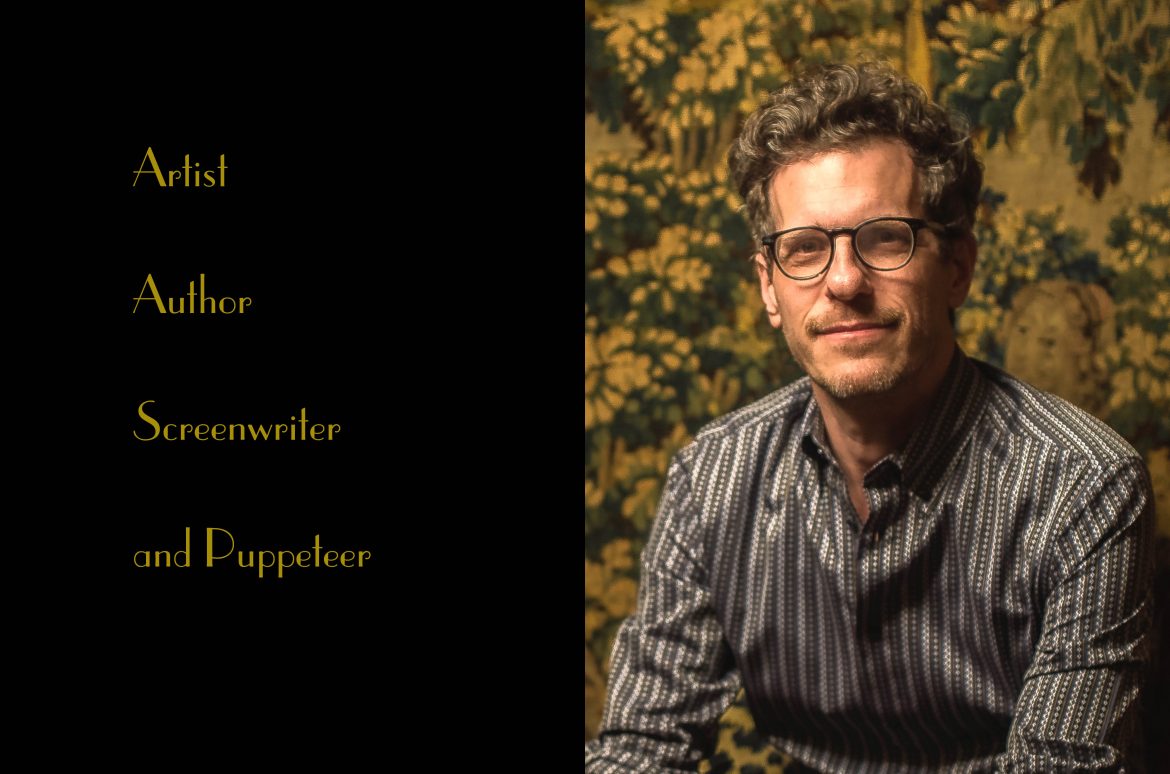

Brian Selznick is a New York Times best-selling children’s book author and illustrator. With scores of books under his belt, it’s probably The Invention of Hugo Cabret that he is most noted for. In fact, he won the coveted Caldecott Award for the book and then it was adapted into the 2011 film, directed by Martin Scorsese, which won 5 Academy awards.

Brian also wrote the screenplay for the film adaptation of his book, Wonderstruck, directed by Todd Haynes (Far From Heaven). And he was commissioned to rewrite the story of The Nutcracker for the Chicago Joffrey Ballet. It’s a timely and stunning retelling of this classic story, which now centers around the immigrants who built the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

To celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Harry Potter books, Brian was selected to create new covers for all 7 books. Most recently Brian illustrated the adult themed book, Live Oak, with Moss, a collection of poems by Walt Whitman. As he was turning forty, Whitman wrote twelve poems that were extremely personal and explored his attraction to, and affection for, other men.

First, we must discuss your book The Invention of Hugo Cabret. Where did the idea for the story come from?

Well, to fully answer that question I have to go all the way back to 1991 when my first book, The Houdini Box was published. That story was about a boy who meets the magician Harry Houdini in 1927, the year Houdini died. Houdini had been a hero of mine when I was a kid, and I wished I could meet him, so the story grew from that idea. I was beginning to think about what my next book could be and I remembered watching the silent film A Trip to the Moon by Georges Melies. I thought writing a story about a boy who meets the man who made that movie would be a good idea too, but I couldn’t think of a plot so I mostly forgot about it. Many years later, after I’d done about fifteen more books, including several picture book biographies, I found myself stuck. I didn’t know what to do next. During this time, I met the great illustrator Maurice Sendak, and he became a mentor to me. He said, “Make the book you most want to make,” and suddenly I remembered A Trip to the Moon. Coincidentally, a few weeks later I came across a review for a book about the history of automatons called Edison’s Eve by Gaby Wood. That’s where I learned Melies had a collection of automatons which were donated to a museum at the end of his life. Supposedly they were destroyed by a leak in the attic roof where they’d been stored, and they were all thrown away. I imagined a boy climbing through the garbage and finding a broken automaton, and the plot began to take shape.

When you’re creating, do the illustrations and visuals come first or the story and characters?

Usually the mechanics of the plot come first. I will often write stories based on places I love or moments in history that intrigue me. I will try to find a character who can move through the elements of the plot, and the last thing I think of is the emotional reason that motivates the character to set the plot in motion. I don’t recommend this to other people, as it seems like I’m mostly working backwards, but it’s how stories usually come to me.

Your book The Invention of Hugo Cabret was a huge success, as was the film adaptation, Hugo. Did you have much involvement with the movie’s production?

Hollywood quite literally came calling! Even before the book was published, movie producers had gotten their hands on early review copies of the book and there was a lot of interest. I’d been making books for a long time and nothing like this had ever happened to me. It was really exciting, but of all the people who reached out to me, there was one letter that stood out. It was from a woman named Grey Rembert who worked for a company I’d never heard of. She said she loved my book so much and wanted to “take care of your orphan.” She’d grown up in a house with an automaton, so she related to the story in many ways. It was a beautiful letter, and I remember thinking this is the person who I want to offer Hugo to. It was only later when I was talking to Grey on the phone that I learned she wanted to give the book to Martin Scorsese to direct. I almost fell out of my chair. I had no real involvement with the making of the movie, but Scorsese loved my book so much he had copies of it all over the set and everyone stuck to it as closely as possible. He even used my drawings like storyboards. Dante Ferretti, the production designer who won his third Oscar for Hugo, had my drawings enlarged and hung all over his office.

Then you created the book Wonderstruck, which was also adapted to film and you wrote the screenplay. Was that an easy or challenging adjustment for you as a writer?

During the making of Hugo I became friends with the incredible costume designer Sandy Powell. She read Wonderstruck soon after it was published and told me she thought it would make a great movie for her friend Todd Haynes. Todd’s movies were some of my favorites, including Far From Heaven and Velvet Goldmine, both of which Sandy had designed. Sandy also encouraged me to write the screenplay myself. I’d also become friends with the screenwriter John Logan who had written the wonderful adaptation of Hugo. He took me under his wing and walked me step by step through the process of writing the screenplay for Wonderstruck. I was incredibly lucky.

How was it working with director Todd Haynes?

Working with Todd was such an incredible dream. He’s a master at every aspect of moviemaking and it was so thrilling to be with him as he spoke with each department in the language of their particular craft. Everyone respected him so much and were proud of their collaborations with him. Most of the team had worked with him many times before, and each department was filled with the most wonderful artists and craftspeople. He also innately understood how to work with Deaf actors, who were integral to the production, so the entire shoot was completely accessible and collaborative. The whole crew were given sign language lessons before we began filming, and there were always interpreters on set. Some of the Deaf actors played hearing characters, so when it was their turn to say a line they needed visual cues, since they could not hear the spoken words. Something as simple as a hand being placed on a hip would be enough of a cue, and the actors all worked together beautifully. I’ve now had the chance to watch Martin Scorsese and Todd Haynes make movies, and those are experiences I will cherish and be grateful for forever.

The Nutcracker! How daunting was it to write a new story for the beloved and classic ballet for the Chicago Joffrey Ballet?

I was honored to be asked by the choreographer and director Christopher Wheeldon to help him conceive a new narrative for the ballet, but I didn’t want to tell him I knew nothing about ballet, The Nutcracker or his own work! So I spent a long crazy weekend watching about twenty Nutcrackers online, and interviews with Chris, and I watched as many of his ballets online as I could. I also bought tickets for An American in Paris on Broadway, which he directed and choreographed. He happened to be attending that performance so we got to meet in person, which was great fun. Our official first meeting for The Nutcracker was a few days later, at which point I had almost tricked myself into thinking I was an expert in what I was saying! By the time I left the meeting we had a few good ideas for me to start thinking about, and within a few days I’d written a 40 page outline for the entire ballet. Chris later said that if he tried to choreograph all of what I’d written the ballet would be fifteen hours long, so we began trimming. It was thrilling to work with Chris because he, like most dancers, had been dancing The Nutcracker since he was a small child and the music was truly in his blood. I’d go to his apartment and sit by his side discussing each moment, and sometimes he’d get up and move across the room to work out a thought or demonstrate an idea, which was magical. Once the outline was finished I was able to go to Chicago to visit him as he built the dance with the brilliant people at the Joffrey. It was such fun to sit in a room watching all of these artist-athletes bringing the story to life. One of my favorite designers, Julian Crouch, created the visual world of the ballet and I had so much fun going to his studio with Chris to look at the models of the sets he and his assistants had built. For anyone who is interested, there’s a documentary online about the making of the ballet.

You had an extraordinary friendship with Maurice Sendak. How did that come about?

I met Maurice at a bookstore where we were both signing books. I was too nervous to speak to him so I asked his assistant if I could have his address, that way I could collect all my thoughts and put them into a letter. A few weeks after I mailed it to him, he called me. We began having long, intriguing phone conversations every few weeks, usually late at night. I was always so nervous when the calls began, but they were so interesting and flowed so naturally that I calmed down after a while. He didn’t know my work so he asked me to send him some of my books. I think I sent him a box with everything I’d published to that point. After he received them he called me and said, “Well, you can draw, which is not true of most illustrators, but none of these books reach the potential I see in you.” That was the beginning of a reassessment of my work which eventually led to The Invention of Hugo Cabret. By the time that book was published Maurice had begun inviting me regularly to his home in Connecticut where we’d go on long walks. After I sent him a finished copy of Hugo he invited me for a visit and took me for a walk. He told me he’d read Hugo and then he paused. “This is the book I was waiting for,” he said. Nothing could have made me more proud. I loved him very much.

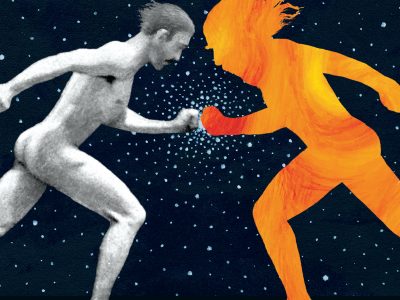

An Illustration from Live Oak with Moss

And this close connection lead to Live Oak, with Moss?

When I met Maurice I’d recently finished a children’s book biography about Walt Whitman, and by coincidence he’d just begun reading Whitman’s poetry for the first time. He told me about a little-known sequence of poems that Whitman had written called Live Oak, with Moss. These twelve poems were about a love affair with another man. Maurice told me Whitman had never published the poems as he wrote them in his lifetime. Instead he cut them up, rearranged them, and hid them in Leaves of Grass, where they remained, unknown, for over a hundred years. Eventually someone discovered them and put them back in their original order. Maurice said he was thinking about illustrating these poems, but he believed poetry, in general, should not be illustrated, since the pictures would interfere in the relationship between the poem and the reader. Pictures, Maurice said, should illuminate a text, expand and complete the words, but poetry did not need this. After Maurice died I lamented the pictures he never made. But a few years later I was approached by my friend Karen Karbiener who is a Whitman scholar. She thought I should illustrate a book to celebrate Whitman’s upcoming 200th anniversary. By this time I’d made an erotic toy theatre puppet show (!) based on the poems, and I thought maybe I could try to turn the poems into a book with pictures. But I remembered what Maurice had said, so I wondered if there was a way to honor his belief that poems should not be illustrated, while illustrating the poems! My solution was to create a long visual sequence that leads up to the poems. My visual sequence is filled with images drawn from the poems: fires, and oak trees, and men’s bodies, but there are other images that come from the themes of the poems and are not literally found in the language. This visual sequence is like a path, and once we get to the poems, all twelve are then presented with no visual interruptions. More drawings continue the journey after the poems end. The images are a framework, or a lens, but they do not illustrate the poems in any traditional sense. I hope Maurice would have approved.

I’m obsessed with your puppetry. (I’m also a huge fan of Basil Twist.) Do you create all of the set pieces, yourself, for the puppet shows?

I’ve done three toy theatre puppet shows: The Christine Jorgensen Story, The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins, and Live Oak, with Moss. I hand built and painted every aspect of these three shows, and I wrote and performed them myself as well. My friend Dan Hurlin directed them, because I felt I needed an outside eye to help me craft them into finished pieces. In quarantine this summer I directed a puppet show that was built by two amazing puppeteers in Chicago. The show, Doll Face Has a Party was based on a book I illustrated in 1993. It’s about a doll who, without leaving her house, throws herself a party and makes her own friends from utensils and kitchen supplies. It seemed like a perfect pandemic story. All four of these shows can be found at my website.

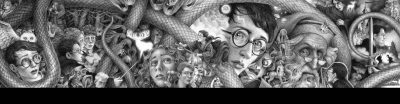

The complete Artwork for all 7 Harry Potter Books

In regard to Harry Potter, did J. K. Rowling approach you about celebrating the 20th anniversary?

On Halloween three years ago, I got a call from some of my friends and collaborators at Scholastic. They told me the 20th anniversary of the first Harry Potter book was coming up and they wanted me to do new covers for all seven books. I almost said no because the project was too overwhelming…I mean, it seemed like the entire world loved Harry Potter. But while we were speaking I had an idea. I could make all seven covers as a single image that would tell the entire story of Harry Potter from his birth to the last chapter of the last book, and I’d do it all in black and white. I had a sketch for them in a week or so, and it was approved very quickly. I had come late to the books but I was already a huge fan when I was invited to do the artwork. As I worked on the final drawing I listened to the audiobooks narrated brilliantly by Jim Dale. It took me about eight full days to do the final art after three months of sketching and photographing models to prepare for it. I finished the drawing as I was listening to the Battle of Hogwarts during the last book. We were in touch with JK Rowling’s team throughout the process. They were very generous with me and wanted me to follow my own vision for the covers. It was quite an experience.

And what is on the horizon for you, Brian? I believe a musical adaptation of Hugo?

Yes, I’m working with Christopher Wheeldon who will direct and choreograph. I’m writing the book and co-writing the lyrics with Ryan Scott Oliver who is also the composer. It’s a really fantastic team. We had a month-long workshop in London right before the world shut down. We are continuing to work on the show via Zoom. Ryan and I are writing a new song right now. I’ve never written lyrics before and I’m learning so much working with him. Usually I write a first draft that has no real structure or rhyme scheme, then Ryan hammers it into a musical shape and sends it back to me, and I rewrite it, keeping to the new structure, and we keep going back and forth till we’re happy with the lyrics. He then sets it to music and sends me a demo to hear how it sounds when sung and we usually do some more rewriting from there. I love the process.

_______________________________

You May Also Like

PASSPORT Profile: Edmund White, Novelist, Memoirist, Essayist, Playwright, and Professor Emeritus