Courage rises with danger, and heroism with resolve. Does not our breath come freer, each heart beat quicker in these rare and grand moments of human life, when all doubt, and wavering, and weakness are cast to the winds, and the soul rises majestic over each petty obstacle, each low, selfish consideration, and, flinging off the fetters of prejudice, bigotry, and egotism, bounds forward into the higher, diviner life of heroism and patriotism, defiant as a conqueror, devoted as a martyr, omnipotent as a deity!

— Jacta Alea Est (The Die is Cast) July, 29 1848, The Nation. Lady Jane Wilde

It’s with a reflective heart that I stand in the corner of Oscar Wilde’s childhood home of 1 Merrion Square. Located on the most fashionable side of Dublin, an area once envied for its location near the Duke of Leinster’s residence. The gracious Georgian townhouse now feels like an empty shell of how I had pictured it before stepping through the front door. After 23 years of being left in disrepair, the American College Dublin worked to completely renovate the property, and, while much credit is due, the College stopped providing tours after a few short years. Now, the building has been completely taken over as a sterile campus. But I am lucky still, as Oscar Wilde Tours provides us access to explore the building, a privilege that few, even the Oscar Wilde Society, enjoy.

I am greeted by one of the few portraits known of Oscar Wilde’s mother, Lady Jane Wilde, the famous nationalist, essayist, and poet, and then by a stunning stained-glass window that represents The Happy Prince. I marvel at how perfectly the arched window represents the themes of the short story—the deep class divides of Victorian times and the visceral struggle of the Irish famine, all done in a Gaudí-meets-Jill Thompson fashion. The sun shines through the blue glass, illuminating snowy dust particles flowing toward a staircase that leads to the second floor. I walk up slowly, picturing a young Oscar Wilde jetting up the stairs just home from school, and I trace my finger along the Georgian-yellow wall. A woman from the college is following closely behind making sure we’re out by the time she has a conference call. “We don’t normally do tours,” she repeats excessively. She bookends each detail she points out with the same phrase: “We’re a private institution.” Ignoring her warnings that we can’t spend too much time, I sit in the corner of Lady Jane Wilde’s parlor. It was in this room that Lady Wilde held her famous gatherings, where the greatest literary and political minds converged in Ireland. It’s here, in this very corner, in which a young Oscar Wilde would have sat quietly and listened to the goings-on of the time, and very likely where Oscar picked up his knack for dialogue, wit, and the powerful sense of observation that he carried with him until the day he died.

Catherine Jane Hamilton once described Lady Wilde as she appeared during this time: “A tall woman, slightly bent with rheumatism, fantastically dressed in a trained black-and-white checked silk gown. From her head floated long white streamers; mixed with ends of scarlet ribbon…Her talent for talk was infectious; everyone talked their best.”

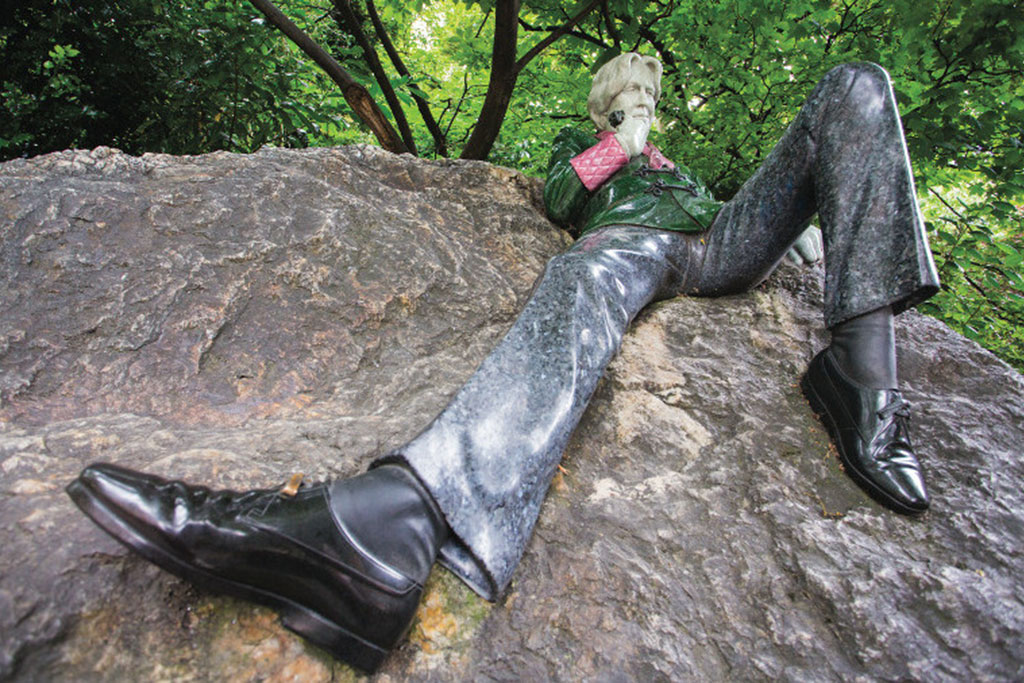

I imagine her sweeping through the parlor. The now near-empty room, only filled with a few chairs and a table for students to study, allows me to fall into a trance-like state, like The Shining ballroom scene, the Wildes’ presence is almost palpable as I imagine the discourse that must have taken place. The salon has a grand view of Merrion Square, one of the city’s toniest parks, and from the corner window, which you can admire from the street, I can see the statue of Oscar Wilde lazing on a rock. In Lady Wilde’s time, the curtains would have remained drawn, as she preferred candlelight, most likely because she was self-conscious about her size.

“Let’s keep going, we simply don’t do tours anymore,” my guide insists. We walk past beautiful sculptures and paintings of Wilde that occupy various nooks and crannies, all gifts from artists still inspired by Oscar. I admire the gorgeous bust by the famous sculptor Melanie le Broquy. We ultimately find ourselves in what would have been the doctor’s office of William Wilde. An acclaimed eye and ear surgeon who was ultimately knighted, as well as a prominent figure in preserving Irish folklore and history, Oscar’s father was not free from scandal himself. As I examine a case of medical instruments that look as though they’ve been taken straight from Michael Kerrigan’s The Instruments of Torture, a professor from Trinity College, Eibhear Walshe encourages us to go outside so he could give us the 19th-century scoop on William Wilde.

As the door is quickly shut and locked behind us by the house’s gatekeeper, Walshe lights up like a dog being let outside for the first time all day. “Right here, on these very steps,” he explains, “A woman by the name of Mary Travers would have been handing out leaflets accusing William Wilde of seducing her.” Travers ultimately brought a libel suit against the Wildes, and he describes the fervor in upper-class Dublin that a trial like this would have caused. No doubt, a ten-year-old Oscar would not have been immune to this gossip, a type of scandal that can easily be seen as a plot staple in his many plays that comment on Victorian English society. The story of Mary Travers isn’t just a one-off anecdote for openly gay Walshe, his fascination with Travers’ story ultimately led him to create a piece of historical fiction based on the woman who nearly destroyed the social standing of the Wildes. His book, The Diary of Mary Travers is currently available for purchase and is a worthwhile interpretation of the scandal.

I’m here in Ireland to take on a chunk of gay history by examining our collective past through the short time that Oscar Wilde spent in Dublin. As part of Oscar Wilde Tours, I’m hoping to discover Dublin through a new perspective, one that’s rarely seen by travelers, and I already have a feeling, while watching tourists peep into the locked house, I’ve picked the right tour.

Andrew Lear, the founder of Oscar Wilde Tours, is enthusiastic in his quest to bring history to life in Dublin, and with the help of some of his friends and colleagues, he does just that. In a brief intro to Dublin, we walk past the home where Wilde was born, just a stone’s throw from 1 Merrion Square in Westland Row. For most, though, they will never see his actual birthplace. The only reminder of Wilde, for the casual tourist, is the monument of him in Merrion Square.

We each have our own opinion on the statue that was erected by the Guinness Ireland Group. But we can agree on the expert crafstmanship. It took nearly two years for sculptor Danny Osborne to create; you’ll understand why when you examine the three different types of stones used. I contemplate how the writer would receive the statue and Ireland’s newfound dedication to the author, especially, after his very public buggery trial that disgraced the family, and to a certain extent Ireland. It’s surprising to think how much Ireland has changed over the years, it would have been unthinkable for the country to embrace the writer after he was accused of sodomy in London, and even his plays were largely left untouched. Even in the early 1990s a monument of this scope wouldn’t have been built, as same-sex relations were only decriminalized in 1993. The statue, unveiled in 1997, is truly a symbol of a changing Ireland.

Upon his return to Dublin in 1883, when he proposed to his soon-to-be-wife Constance while lecturing at the Gaiety Theatre, Wilde chose to check into the only hotel fit for a newly minted Londoner, The Shelbourne. Therefore, it’s only fitting that I too stay in this gorgeous, historical property that immediately transports travelers back in time to the glamour and exclusivity of turn-of-the-century travel. The hotel was extensively renovated in 2007, so the rooms don’t feel stuffy, but rather lavish and modern. This came as a surprise to me after I heard the property was dubbed “The Grand Old Lady of Stephen’s Green.”

We’re eager to check out another of the city’s grand dame properties, The Merrion Hotel to enjoy a time-honored tradition, high tea. We first examine the hotel’s elaborate art collection that adorns the walls of the drawing rooms. One of the most extensive private collections in Dublin, the hotel has pieces from artists J.B. Yeats, William Scott, and Louis le Brocquy. I love the springtime flowers that create a bed of color in the courtyard, as Rowan Gillespie’s Ripples of Ulysses statue of James Joyce proudly looks over. Lear’s tours blend these high-end, let-loose experiences with more academic tours, and it’s nice to get to know everyone in our group over the best tea in Dublin.

“Straight society does its best to ignore gay history, and while most gay people are pretty interested in it, the information isn’t easily available even to them,” Lear tells us, as we sip our tea and nibble on the first course of tea sandwiches and scones drowning in clotted cream. “So, we founded Oscar Wilde Tours to try to change that,” he says carefully trying to avoid getting crumbs on his smoking jacket.

As we continue to dive further into the story of his new tour company and discuss more about Oscar Wilde in general, I’m thankful I paid attention to the surrounding pieces of artwork, as the second course draws from the in-house art collection. Our server cheerfully brings over a colorful tray of cakes, along with accompanying Tarot-like cards that show which paintings the chef drew inspiration from. I delicately take apart a rosewater and orange mousse on a white chocolate feuilletine based on a painting by Patrick Hennessy called Roses and Temple. I feel almost guilty destroying its beauty. I look around the room that’s filled with a mix of “ladies who lunch” and a handful of gay men, and feel as though the room is exactly where you’d expect to find a sociable Wilde.

During the tea, Lear also hands us green carnations, a de facto symbol for both Wilde and homosexuality. As we place them through our buttonholes, Lear reminds us that during the first performance of Lady Windermere’s Fan, Wilde encouraged an actor to wear a green carnation, and also insisted his friends sport the flower as well, which would have been dyed with arsenic in Victorian times. While Wilde contended the flower meant “Nothing whatever…” it became a vibrant symbol of queer culture. “Pretty boys, witty boys too, too, too…and we all wore a green carnation,” Noël Coward wrote in Bitter Sweet in 1929 showing the long-lasting effect of this symbolic gesture, and we proudly sport ours throughout the trip. After a couple of days in Dublin with Lear, I am filled with excitement about what’s to come next.

Lear arranges for our group to meet with Brian Merriman, the founder of the International Dublin Gay and Lesbian Theatre Festival which is currently going on. Despite the chaos of running this large-scale endeavor, Merriman takes the time to sit down with us to discuss both the festival and Ireland’s gay theater history. Gay theatre actually existed for quite some time in Dublin, he begins to tell us, when a gay couple, Hilton Edwards and Micheál MacLiammóir, opened up the Gate Theatre in 1928. “Born in London, MacLiammóir met Hilton, learned Irish, changed his name to Irish, and they lived as an openly gay couple,” he explains to our astonishment. The two were responsible for bringing European and American theater to the city. “Everyone knew they were partners, and they were made Freeman of the City, although they couldn’t get married,” he says. There are great parallels between MacLiammóir and Wilde as Merriman notes in his book Wilde Stages in Dublin, “[MacLiammóir] also adopted a bit of the larger than life persona of Wilde, as many an actor has imitated since. It implies class and intellect, and the pace of conversational delivery emphasizes that point, as does the deliberate broadening of vowels.”

That’s not to say that the couple wasn’t treated any differently by society, Merriman notes: “[They]…were strong in their presentation of historical, Shakespearian, and romantic characters for decades in theatre and yet they were known as ‘The Boys.’ Boys don’t run theatre companies, avoid bankruptcy, persuade investors, employ artists, and establish and sustain a national theatre at The Gate…But ‘boys,’ the talented young men drawn to the escapism of theatre in a hostile society, knew no matter what your status or achievement, a gay artist could never be a man, but remained a ‘boy’ forever.”

Attitudes, and society as a whole, changed later in their lives. While sodomy laws were still on the book in the 1970s when MacLiammóir died, in a grand gesture, to show how important he was to growing the culture of the city, the president of Ireland attended his funeral, while Edwards served as chief mourner. Their legacy continues to live on in the city, as the Gates Theatre is still wowing audiences, and will eventually wow me with their production of An Ideal Husband.

“In so many ways, theatre created a ‘safe haven’ for gay people, on stage or behind the scenes…” he says. And this escapism is a big reason for the creation of the festival, which has its beginnings in 2004. It wasn’t an easy ride for Merriman who tells about how difficult it was to even cast a production of La Cage Aux Folles. Besides sponsorships and fundraisers, an unimaginable thing in 2004, he tells us the festival is beginning to be embraced by “straight” people who have both volunteered and attended the international offerings. It has recently seen more support from the government and the city. Support can be seen further by looking at the banners featuring a picture of Wilde outside of Dublin Castle (these same posters also once greeted passengers arriving at the airport).

Step this way,” Assistant Junior Dean Joseph O’Gorman from Trinity College, one of the most prestigious colleges in Europe, tells us in a BBC-like accent as we try our best to stay out of a passing storm. O’Gorman, who is dressed like a proper dandy, complete with a pocket square, matching suit, a cane, and perfectly round glasses, takes us around the campus. Wilde attended university here from 1871-1874 and chose to live on campus his second year, despite his family home being only a few short blocks away. O’Gorman points out a quad that had been dubbed Botany Bay, because of its less-than-ideal location, but its green lawn and ivy-covered windows makes it seem more like a storybook castle to modern-day observers. O’Gorman is a thrilling storyteller and happily shows us Trinity’s main attractions that are open to the public, including The Book of Kells. As one of the most precious artifacts from medieval times, deciphering the magnificent artworks’ symbols comes second-hand to O’Gorman, so much so, that our small group soon added a few extra members who were eager to listen. He then takes us to Trinity’s Old Library, which is an architectural feat with its barreled ceiling and windows that illuminate the centuries-old books. O’Gorman tells us about the unique challenges of preserving a collection of books this old, including how climate change is threatening their preservation.