When still a teenager, Steven Caras (stevencaras.com) left his home in Northern New Jersey for New York City in hopes of a life in the world of ballet.

Eventually, George Balanchine, who most regard as the greatest contemporary choreographer of the 20th century, took him under his wing. For 14 years Steve danced with New York City Ballet, but eventually, as with all dancers, he knew the day would come when he would have to shift gears.

But what would he do? As a hobby, he taught himself photography and Balanchine welcomed and encouraged him to photograph the dancers and the dances— backstage, during rehearsals, opening nights, even Balanchine’s final bow.

Being an exceptional dancer himself, Steve knew exactly when to take a shot: the perfect line, the tilt of a head, the full extension of a leg. His work is breathtaking, so much so that an Emmy award winning documentary was created about his life: See Them Dance.

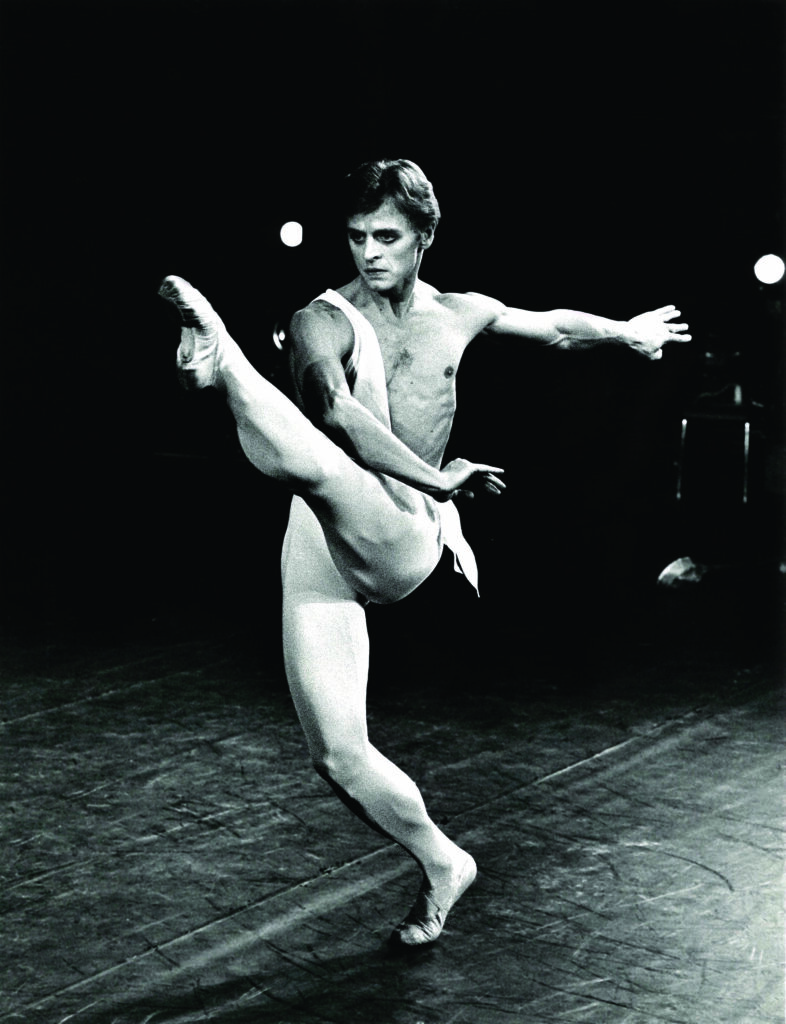

Baryshnikov in Apollo (1979). Choreography by George Balanchine (Photo by Caras)

Because of Steven, we have a pictorial archive of over 100,000 photos of some of the world’s most amazing stars of the ballet world, the likes of Mikhail Baryshnikov, Sean Lavery, Peter Martins, Suzanne Farrell, and Jacques d’Amboise, as well as many more.

When did your fascination with dance begin? Did you see a ballet one day and say, “I want to do that,” or did you know someone who was a dancer?

Thanks to the Ed Sullivan show, I discovered dance when I was about nine years old. My mom spotted her middle son’s fascination before asking if I wanted ballet lessons. Knowing too well how unapproving dad would’ve been, never mind my male classmates, I passed. But passing on training in public didn’t keep me from practicing some novel moves of my own in the privacy of the Caras family basement. This went on for years before I gathered enough courage to audition for our high school’s annual musical. As a singing sophomore I fell flat, but as a dancer, just the opposite, straightaway I was cast as a soloist in Brigadoon.

Soon after that show, you began taking more big chances.

Indeed! Just days following our final Brigadoon performance, I signed up for two ballet lessons a week at the River Edge School of the Dance. In the course of the months that followed, I’d heard buzz among fellow students that the American Ballet Center in New York City (the formal school connected to the Joffrey Ballet) was holding tryouts for summer scholarships. I jumped on a bus, then a subway, heading straight to Greenwich Village to meet my fate. I was awarded a full scholarship, soon to be under the watchful eye of Joffrey instructors, six days a week and for the entire coming year.

To be accepted into the New York City Ballet under the guidance of its founder, Mr. George Balanchine, that must have been exhilarating and absolutely terrifying.

During my time at the Joffrey school, I attended a performance of the New York City Ballet at Lincoln Center. They danced George Balanchine’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream; what a life-changer this turned out to be in all possible ways. That spring, I auditioned for their academy, the School of American Ballet, where I was granted a full scholarship, albeit with conditions: “You’re old [16] but you have good movement quality. We’ll place you in the intermediate level for twelve months. If you show significant improvement, we’ll keep you on.” Less than two years later, I was invited by George Balanchine to join the New York City Ballet.

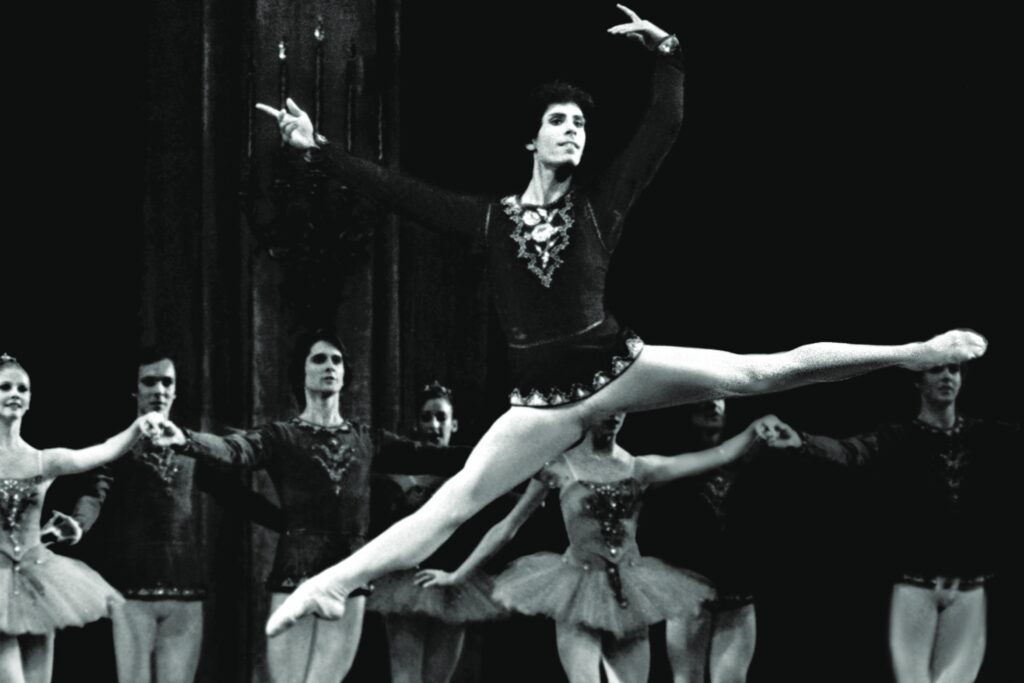

Caras Dancing in Balanchine’s Tchaikovsky Suite No. 3 (Late 70s) (Photo by Costas)

For the next 14 years you danced non-stop. What kind of toll does that take on your body?

The transition from full-time student to full- time professional is enormous, both physically and emotionally. But the “runner’s high” we dancers strive for was thankfully achieved, and I was soon sailing nightly with the artists whom I’d so admired.

So, at what point did you realize you had to ease out of the dancing and how did the photography come into focus? About nine or so years after joining City Ballet, during my recovery from a sprained ankle, I bought a used 35mm camera. Mr. Balanchine was fast to notice, soon scrutinizing my very first shots before promptly granting me full access to capture his otherwise private world—hence the birth of my passion for recording his glorious company. However I was far from ready to make my exit as a dancer. Fortunately, Balanchine was adamant in my not doing so until he felt that I could fully support myself as a photographer. Nonetheless, in the course of the coming few years, I began stepping down from some of the more demanding ballets, devoting that time to the increasing needs City Ballet and various publications had for my photographic work.

Mr. “B” was very encouraging, yes?

Mr. B was beyond encouraging. He had as great an eye for photography as he did for dance. His critique of my images was no different than his critique of my dancing. Always more to learn, always room for improvement, but he was the first to congratulate me when I got it right. And he insisted I made sure to always be fully compensated. “Photography is a profession,” he asserted. A profession many take advantage of.”

You had access to the crème de la crème of the dancing stars at NYC Ballet.

Again thanks to Mr. B, I had carte blanche to photograph all classes, rehearsals, and performances, and from any and all vantage points.

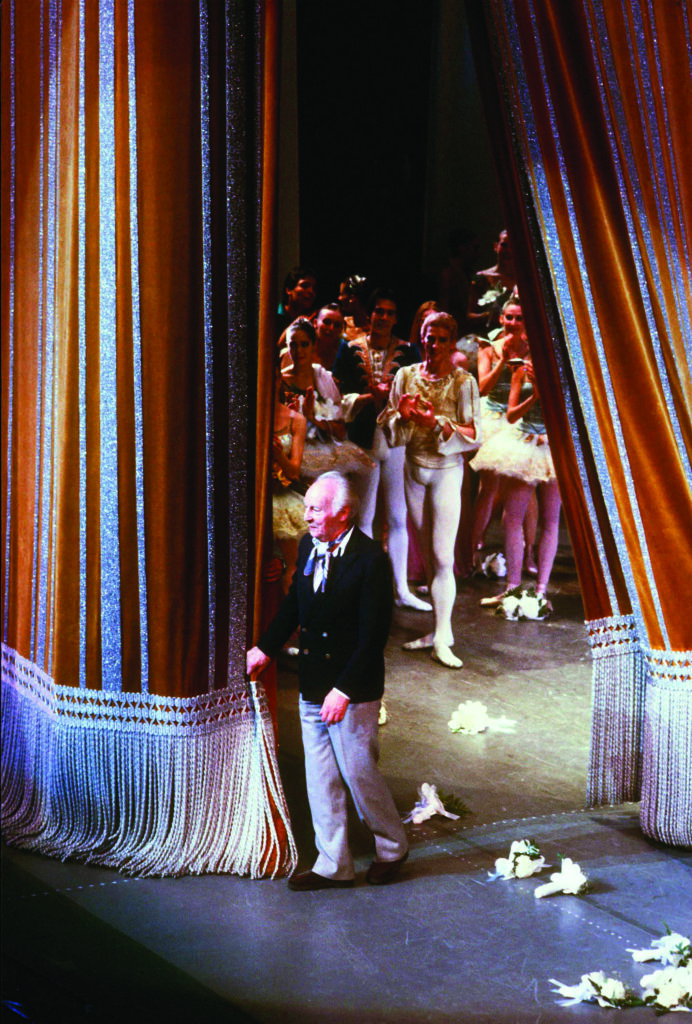

The very first time I saw your work, it was hanging in Sean Lavery’s apartment. I remember standing there in awe as I witnessed Mr. Balanchine’s final bow and behind him the curtain was pulled to the side and backstage you could see Sean and the rest of the ballet company. The photo is kinetic, alive, and extremely moving. Did you take that from the first balcony?

Thank you, Arthur. And yes, it was taken from the first balcony. It was the first year I wasn’t behind that very curtain with fellow dancers, encouraging Mr. Balanchine to take his traditional, closing night bow. It was July 4th, 1982. Nine months later, Mr. B was gone. I named the image Last Bow.

Last Bow, July 4, 1982 (Photo by Caras)

Were any of the dancers reluctant to have you standing in the wings photographing them? Did it make any of them nervous or self-conscious?

Not at all. In fact, just the opposite. We were family, hence they trusted me implicitly.

At what point did you completely stop dancing and devote your full attention to your photography career.

When Balanchine was showing up a lot less often due to his declining health, I saw this as the ultimate time, however tough, to surrender my place of honor as a dancer. The few times I’d tried before, Mr. B insisted I continue overlapping both careers, as he was very much concerned that I’d have a difficult time sup- porting myself solely as a photographer.

Tell us about your career as a photographer since then.

I segued into portrait work in the early to mid-1980’s, at first converting my living room into a studio. Since those days, I have used various studios with the many dance companies and academies with whom I’ve worked. When taking on other assignments, such as fashion and portraiture, when not on location, I rent formal spaces.

You’re also a sought-after speaker and interviewer.

Thanks. To my full surprise, this started over twenty years ago on a day when I was asked to step in last-minute for the artistic director of a ballet company. It’s never let up since.

How does stepping in last minute for the artistic director of a ballet company make you a sought-speaker and interviewer?

Via word of mouth and over time. Early topics and interviewees were directly related to dance. And those who engaged me to speak made it clear that they trusted me to take charge since I’d “walked the walk.” Eventually I grew less nervous, in due course hosting interviews with guests not involved in dance whatsoever, some of whom including sex therapist and talk show host, Dr. Ruth; singer pianist, and music revivalist, Michael Feinstein; businesswoman, interior designer, and fashion icon Iris Apfel, best-selling author Scott Eyman, and skincare industry pioneer, Adrien Arpel.

How did it feel to have the PBS documentary of your life as a dancer and photographer Steven Caras: See Them Dance, win an Emmy?

In a word, surreal. To say that being presented with an Emmy Award is equal parts humbling and prideful would be an enormous understatement. Yet it was the third Emmy that documentary filmmakers John Witek and Deborah Novak (Witek & Novak) had received. When Deborah, a dancer herself, had first approached me with this idea of hers, I had some doubts. But after sharing that she’d been following my career since my Billy Elliot beginnings,” I knew I’d be in good hands. The film aired nationwide from 2011 through 2014.

And in 2014 you received the Career Transition for Dancers’ Heart & Soul Award, presented to you by the beloved Chita Rivera. Can you explain more?

In the course of the documentary’s third year of airings, I was contacted by the CTFD, asking if I’d be willing to accept their lifetime achievement award. No time needed to ponder that generous surprise. And if this wasn’t enough tremendous news to digest, of all people, Chita Rivera (who also trained at the School of Ameri- can Ballet), was to be the evening’s official host and award presenter. Needless to say, it was a thrilling occasion, not only by receiving the honor while sharing the stage for a few fleeting moments with the one and only Chita, but later spending a lot more time with her on the dance floor.

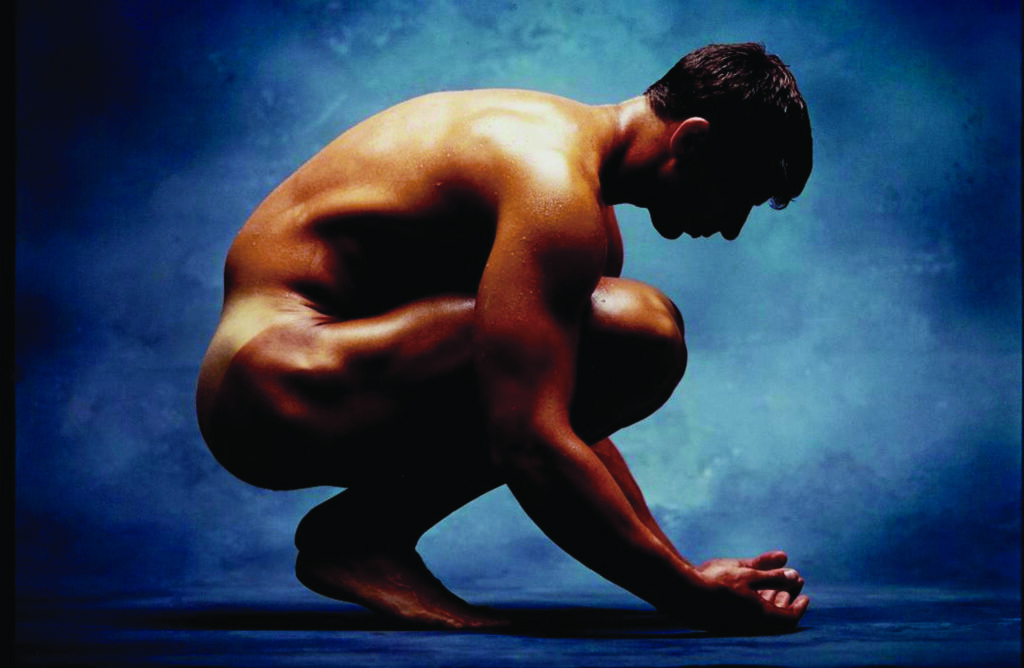

Leroy Robert 1995 (Photo by Caras)

Tell us about the Steven Caras Achievement Award for Promoting, Preserving & Perpetuating Dance. What an honor! Yes, a serious honor to be sure. At Boca Ballet Theatre’s annual gala in January of 2023, the organization gifted me with their inaugural Steven Caras Achievement Award for Promoting, Preserving & Perpetuating Dance. In January of ’24, they honored me all the more in asking that I join them in naming New York City Ballet Principal Dancer, Daniel Ulbricht, as the second recipient of this annual prize, which includes a statue of my likeness as a dancer along with a generous monetary gift.

Tell us more about your current work with Rosie’s Theater Kids in Manhattan.

My name falls under the title, Advocacy and Outreach, but to be honest, Team Player would suit me just fine. Following my rehearsal director work with several ballet companies, I went on to serve in head of development positions (Miami City Ballet, Palm Beach Dramaworks). As a result, Rosie’s exceptional director, for- mer dancer Lori Klinger, expected I’d be a good fit for them. We all wear many hats at Rosie’s which, in my opinion, is one of New York City’s most important outreach programs. While we teach young kids to sing, act, and dance, our tagline, “We’re rehearsing for life,” says so much more. Big thanks to Rosie O’Donnell for recognizing the importance of such a program and for doing some- thing about it. This month marks my eighth year with the organization.

Any other upcoming news we should share with our readers?

I’m especially grateful that my current exhibition, CARASMATIC: Through the Lens of a Dancer, will remain at The Raymond F. Kravis Center for the Performing Arts in West Palm Beach through (at least) December of 2024. It includes 80-plus images, spanning over forty-five years.