The intense green of the foliage. The impossible blue of the ocean. The Brazilian boys swinging across a swimming hole, a parade of young Tarzans. Like Tony meeting Maria in West Side Story, I was smitten by Ubatuba at first sight.

Last winter, I went to Brazil. It was a trip that began five years prior, in Paris. While reporting on the 2018 Gay Games, I crossed paths with a Brazilian journalist, Felipe Abilio at a press conference. I mentioned that I loved Brazil, having visited Iguazu Falls on the Argentinian border and twice spent time in Rio de Janeiro.

“And I’ve been to Floripa!” I boasted, dropping the locals’ nickname for Florianapolis, a beach-encircled city on coastal Santa Caterina island 700 miles south of Rio. I expected this to impress him, given Americans’ general obliviousness to the destination.

“Is nice,” he replied in rudimentary, heavily accented English. “But I am from the most beautiful place in all of Brazil.”

“Where’s that?” I asked. He hurriedly sent me a link to his Instagram before we headed off to separate athletic events.

“You’ll see,” he remarked, stepping into a revolving door, light sparkling off his septum piercing as he spoke in what sounded like babytalk: “Ubatuba.”

I can think of few other places in the world that could pull my gaze away from a water polo match between the West Hollywood Aquatics and San Francisco Tsunami, but there I sat, in the bleachers of a Paris natatorium, fixated on my phone like a Scruffing twink in the midst of a dance club.

Art at the Airport in Sao Paulo (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

The intense green of the foliage. The impossible blue of the ocean. The Brazilian boys swinging across a swimming hole, a parade of young Tarzans. Like Tony meeting Maria in West Side Story, I was smitten by Ubatuba at first sight.

Unlike Tony and Maria, whose relationship was brief and doomed, U. and I were bound for a slow-burning, internet-stoked long-distance affair. Half a planet, lots of planning and a pandemic came between us.

But the mere anticipation of fabulous travel can be a powerful mood enhancer. My Ubatuba obsession gave my partner John and I something to look forward to through the coronavirus years. It was time-release catnip, a light we imagined at the end of the tunnel.

Ubatuba is situated on the state of São Paolo’s Litoral Norte, or north coast, cradled between the ocean and thickly forested Serra do Mar State Park. Known as the surfing capital of Brazil, it boasts over 100 beaches (more than one for every 1,000 residents) across an archipelago of largely uninhabited small islands, including a protected marine sanctuary.

It’s one of many welcoming, but mostly undeveloped towns in this region. They’re well known to Brazilians but relatively undiscovered by international travelers. The easygoing, no-stress vibe and raw natural beauty of the Litoral Norte is reminiscent of eastern Mexico’s Riviera Maya in the 1980s, before it became an overpriced, over-Americanized resort hub.

Just as Brazil’s seductive version of the Portuguese language lets individual words elide into a single flowing stream, the country’s governmental geography has its own slippery overlaps: Ubatuba is both a city proper and a larger region within the Litoral Norte, and it is only 150 miles from the city of São Paulo. To me Ubatuba had grown beyond a city or region to become an all-encompassing vacation state of mind. The destination was an excuse for the journey.

WELCOMING LGBTQ+ TRAVELERS

Dashing Brazi-daddy Clovis Casemiro, a São Paulo resident, is his country’s lead representative to the International Gay and Lesbian Travel Association (IGLTA). For years, he has led successful efforts to assure that his homeland and its hospitality industry extend a warm and sincere welcome to the world’s queer community.

Before pandemic travel restrictions had even been lifted, I reached out to him with questions about planning our trip: Was the country still friendly to gay travelers despite the authoritarian administration of then-President Jair Bolsonaro? For travelers from the U.S. who had previously experienced the excitement of Rio, would the city of São Paulo and the nearby coast offer a worthy return to Brazil? And could he provide any guidance on visiting my lodestar, Ubatuba. He replied “Yes!”, “Yes!” and “Hmmmm…”

While the Brazilian government leaned conservative during the Bolsonaro presidency (2019–2022), enacting policies that were anti-environmental and anti-indigenous people, it also oversaw a dramatic decrease in crime, a frequent concern among foreign tourists.

Ubaflora (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

And the country, now moving slightly leftward after the 2023 inauguration of Lula da Silva (previously president for two terms, from 2003 to 2010), has same sex marriage and adoption rights as well as public healthcare funding for gender affirmation surgery.

Clovis was more than enthusiastic about my suggestion of bypassing Rio. The Cidade Maravilhosa (Marvelous City) with its landmarks of Sugarloaf, Copacabana Beach and mountaintop Christ the Redeemer, isinarguably alluring, but itsfame has obscured other worthy destinationsin thisimmense country, 86% the size of the United States.

“There are so many amazing places to explore,” enthused Clovis, ticking through a list that included the African-influenced colonial city of Salvador; the Amazon gateway, Manaus; and the island of Noronha with its annual upscale international queer festival of culture and gastronomy.

“And of course, São Paulo, which has amazing food, nightlife, and some of the best beaches in the world.” (Again, visitors should be mindful of city/state blur: São Paulo, the hard-partying city, is landlocked; the beaches, in the state of São Paolo, offer plenty of daytime adventure and gay-friendly stays, but little in the way of nightlife or queer-specific venues. You want to hit both).

The matter of Ubatuba, however, stopped Clovis cold. “How did you even hear about it?” wondered this bona fide ambassador for queer Brazil, sounding a bit wary.

“I met a guy from there a few years ago. He posts fantastic videos online. Once I’d heard that there was a place that was actually called Ubatuba,” I explained, “and then saw that this place with the ridiculous name was also ridiculously gorgeous, I just had to get there.”

“I’ll see what can be arranged,” he promised.

FIRST STOP: UNIQUE CHIC IN SÃO PAULO

When John and I arrived in São Paulo on a Friday night, nearly a half decade after Mission Ubatuba was hatched in my mind, we were greeted at the airport by Marcelo Michieletto, the sparkle-eyed proprietor of the MH Tour travel agency, who Clovis had pointed us to as an ideal fixer for exploring the nearby coast.

As it turned out Marcelo was ideal in a million ways, the best and most engaged travel professional I’ve ever had the opportunity to work with, anywhere in the world. A cheerful man of many hats (and at least as many oversized designer eyeglass frames), he’s a former lawyer, publisher of Brazil’s queer lifestyle magazine BeFree, and an intrepid traveler himself (His favorite foreign destination: Scotland, land of misty peaks and bears in skirts; pretty much the antithesis of his own country). He proved unendingly generous with his time, perspective, and enthusiasm.

São Paulo’s infamous traffic was immediately evident. On the hour long drive into the city center, Marcelo’s sedan was surrounded by 18-wheel big rigs. The highways of São Paulo, larger than New York and even Mexico City, with a population of over 21 million, are so congested with commuter traffic by day that long-haul truckers aim to traverse the metropolitan area after dark.

Having worked with Marcelo to organize a coastal itinerary of relatively simple hotels amid splendid natural settings, we’d decided to indulge on our trip’s first weekend. Over many idle hours of pandemic Instagram scrolling, I’d added a second Brazilian obsession to Ubatuba, and it was there that I’d had our new friend book us: The Hotel Unique.

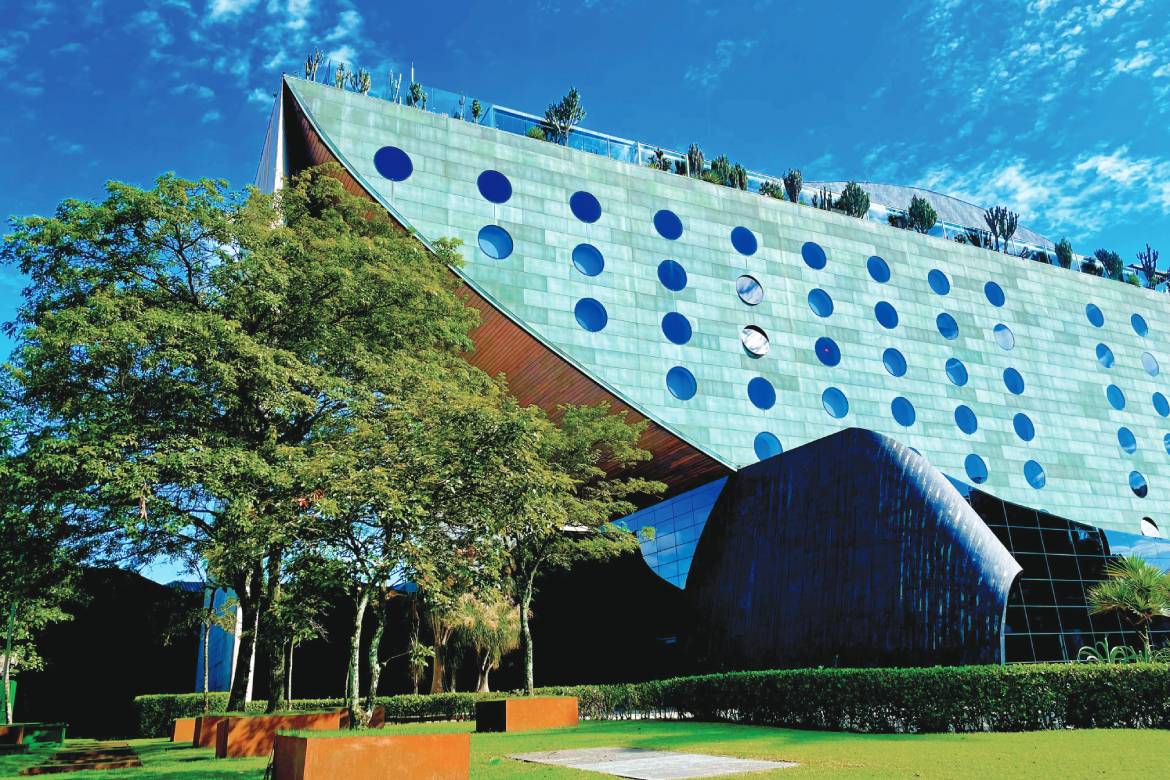

Hotel Unique Exterior (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

True to its name, this five-star 95-room astonishment by Brazilian-Japanese architect Ruy Ohtake offers surprises at every turn. Its main copper-clad structure, perforated with circular windows, is an upside down arch that evokes a child’s simple drawing of a boat or a seed-pocked papaya slice.

The curving exterior wall results in guest rooms at the far end of each floor that feel like slumber parties in a skate park, with beds at the base of sleek wooden ramps. The hallways are dark and wide, with round blasts of sunshine flooding the windows by day. The lobby features ceiling-hung sculptures, aerodynamic furniture, and a bar area with a giant velveteen floor pillow that invites tipsy sprawling.

Two stories below ground are bright blue and yellow lap pools, the latter at the bottom of giant silver sliding board, accessed by a staircase that seems suspended midair.

On the roof is yet a third pool, this one with a crimson-painted bottom and complementary red lighting to create a club vibe by night, a throbbing oasis with 360° views of São Paulo’s gleaming infinity of skyscrapers.

Adjacent to the pool deck, a glass walled interior stretches the remaining length of the roof, housing the restaurant, Skye. For lunch and dinner, there’s a peculiar something-for-everyone menu that spans from croque madames and pizza to elaborately plated dishes like steamed seabass with caviar and champagne cream.

I’d recommend the least complex preparations: Impeccably fresh sashimi and a dessert of tissue-thin pineapple carpaccio dolloped with mascarpone cheese and drizzled with with ginger-orange syrup.

COSMOPOLITAN ENERGY

Located in São Paolo’s upscale residential Jardins district, Hotel Unique is just a few blocks’ walk from Ibirapuera Park, the city’s biggest public green. Larger than Hyde Park in London, it serves as the backyard, athletic field, picnic area, and lovers’ lane for millions of Paulistanos, the vast majority of whom live in compact apartments. It’s estimated that, on an average weekend, over 200,000 people visit the park.

Ubatuba Boatyard (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

Ambling along one of Ibirapuera’s gently curving walkways, John and I observed parents pushing babies in carriages, seniors practicing tai chi, massive group yoga sessions, capoeira classes, bike riders, balloon sellers, roller bladers, sun tanners, slack line walkers, and swan feeders. There was even a small field commandeered by hardcore Quidditch players, awkwardly running with broomsticks clenched between their thighs.

A Japanese garden, a world class modern art museum and a museum of Afro-Brazilian history are among the park’s many cultural institutions. Perhaps most impressive is architect Oscar Niemeyer’s Ibirapurera Auditiorium, a stark white trapezoid sticking its bright red tongue at the sky.

But there’s no better activity here than simply reveling in the people in motion, the strolling soul of the park and the city. Humanity in every hue of brown and beige and tan and taupe and cream and caramel and copper.

There’s no denying the worldwide persistence of ethnic prejudice, but in Brazil, more than back home, colors have actually melded in the melting pot. The citizens of São Paolo have descended, and been blended, from Portugese, Italians,Africans, Syrians, Lebanese, and Japanese, along with indigenousArapaso, Tumbalalá, Almoré and more. It looks like the future.

São Paulo’s other great people-watching promenade is Avenida Paulista, a broad-sidewalked two mile stretch of cosmopolitan energy, lined with banks, theaters, offices, museums, and shopping malls.

The main thoroughfare for June’s annual Pride parade, the world’s largest with attendance estimated at 3 million, Avenida Paulista runs perpendicular to 7-block long Frei Caneca, Sao Paulo’s most central gay neighborhood.

In the thumping heart of the city, same sex couples walk hand-inhand and queer singles unabashedly cruise at the cafés, bars, and bodyconscious clothing boutiques along this street.

Shop for stylish but reasonably priced club wear at Antrato Rouparia or Uzo by day and return after dark to show it off on the dancefloors at Aloka or nearby Club Yacht, with its sailor-suited staff.

Like some grittier iteration of the Champs-Élysées, Avenida Paulista plays host to luxury boutiques alongside traditional basket weavers’ makeshift kiosks, and ladies in couture glancing side-eye at a busking Elvis impersonator. Mirrored contemporary condo towers are interspersed with hulking concrete apartment blocks that date back to the 1970s, their exteriors gridded with window unit air conditioners, still common in this frequently sweltering city.

Colonnaded early 20th century mansions have been converted to corporate headquarters, galleries, and an obnoxious folly of a McDonald’s.

The avenue’s best known landmark is the modern art museum, MASP, a Brutalist glass box suspended a full floor above the pavement by massive red red pillars, designed by Italian immigrant Lina Bo Bardi.

Step into the vast field of shade beneath this floating gallery to escape the sun, then wander back out to the rear plaza for a startling view of this literally layered city: Freeways tangle above and below, rushing through concrete canyons and stands of trees.

And on what seems like every available surface, gargantuan color drenched murals seem to turn the whole of São Paulo into a meta gallery, grander and more energized than any single museum.

TASTES OF BRAZIL

After our afternoon of overstimulation on the streets of São Paulo, John and I spiffed up and slipped into the soothing dark ambience of D.O.M., one of Brazil’s most celebrated restaurants for over two decades. (Its name stands for Dominus Optimus Maximus: “the best and most representative” in Latin).

The flagship project of Chef Alex Atala, whose global reputation has grown multifold after he was profiled on the Netflix series A Chef’s Table, is a showcase for native Brazilian ingredients, some found nowhere else in the world, prepared using the techniques of haute cuisine and molecular gastronomy.

It takes trust to venture into a tasting menu that opens with an amuse bouche topped with a flash fried ant, then moves through courses made with unfamiliar ingredients including earthy black tucupi, the juice pressed from fresh manioc root (quite toxic if not thoroughly boiled); filets of Amazonian pirarucu, one of the world’s largest-freshwater fish; and the sweet-and-sour white flesh of bacuri fruit.

But your confidence in Atala and his team is well-merited. This is no stunt meal, but a delicious edible education. Quick with a quip but never pedantic, servers provide fascinating insights into each dish, many of which have origins in the cuisine of centuries-old rural communities that Atala now helps sustain by investing in their produce.

Perhaps the greatest surprise of our meal is D.O.M.’s açai. Better known to both Brazilians and Americans as a deep purple frozen treat, sorbet-like in texture and served in fruit salad, acai at D.O.M. is served much closer to its natural state: an almost-black palm berry with an earthy, bitter taste. Here, the pulp was pureed, salted, and served in restrained smears as a complement to fish, tasting more like olives than dessert. Those “healthy” bowls you order for lunch are packed with

added sugar.

After dinner, we meet up with Marcelo in the bohemian Vila Madelena neighborhood to sample two more Brazilian specialties: cachaça, the national liquor, made from fermented sugar cane juice; and one of the country’s many musical traditions.

At Bar Samba, one long bric-a-brac covered wall of the alley-like space is lined with patrons seated elbow-to-elbow around small tables. Across the room, a raised platform is crowded with nine exuberant musicians.

Between the two, a mass of joyful dancers sway and rump shake to hypnotic African-influenced beats played on guitar, hand drums, a wood block, rattles, and a tambourine.

Call and response chants begin with the lead sambista and other band members, but are quickly taken up by the entire pulsing crowd. Feeling festive and unfettered, Ubatubular, one might say!, we join the throng, dancing in clusters more than couples, gender rendered irrelevant by a sense of communal celebration.

The energy is artisanally immersive, more ritual than sexual, and so much more fun than the familiar horndog skulking and Lady Gaga tunes we find hours later at the São Paulo Eagle (Let’s face facts: In their all-too familiar global consistency, Eagle bars have become the dark McDonalds of the gay world). When in Brazil, seek a new kind of thrill.

At the top of that list would be a night of carousing in the city’s densest gay neighborhood, Largo do Arouche. The center of the action is the last block of Avenida Vieira de Carvalho, adjacent to Praça Republique (Republic Square). The street is lined with gay bars including Soda Pop, Bar do Lula, G Bar and Silver Mug, but choosing your favorite is not at all a necessity. Their interiors are tiny, so most patrons prefer to stand around outside forming a single, amorphous crowd that spreads across their storefronts, growing into the hundreds after 10 P.M. Servers from each bar wade into the sweaty chatty morass to take and deliver drink orders, but which establishment they work for matters little to the revelers. The people are the attraction here and they’re not hesitant to lean into interesting overheard conversations and make some new friends.

Men from their twenties to their sixties mix freely, wearing anything from leather and chains to glittery eyeshadow and fishnets. It’s a refreshingly democratic scene, with far less clique-ishness and much more camaraderie that one senses in most American cities.

After midnight, head out to nearby Bar Queen, where the go-go boys are famously forthright; the Bubu Lounge disco across town; or the clubs along Frei Caneca. Bigger, a monthly bear dance party featuring sexy go-go dancers and circuit DJs, is among the more popular events that float between venues.

Before heading out of the the city the next day in search of coastal utopia, we get together with Clovis of the IGLTA for lunch at Mocotó, a restaurant in north Såo Paulo that he insisted could not be missed. An ideal culinary counterpoint to ultra-contemporary D.O.M., Mocotó features the traditional sertaneja cuisine of arid northeastern Brazil.

Family owned and operated since 1973, its chatter-filled maroon and yellow dining rooms feel like a never-ending neighborhood party. Tables are packed with families and large groups of friends. Movie-star handsome chef-proprietor Rodrigo and his diverse, friendly staff warmly welcome the queer community.

A highlight among the signature dishes we shared (portions are huge) was slow-cooked beef atolado, a rich stew with bright acidic notes from pearl onions, hunks of pickled pumpkin, green olives, and cherry tomatoes. Slow-cooked in an earthenware vessel, it’s served over couscous like farofa.

Also not to be missed: grilled coalho cheese drizzled with molasses and dadinhos de tapioca, crisp-on-the-outside, chewy-on-the-inside cubes of salty cheese and cassava flour. Both are perfect starters paired with beer or a capirinha cocktail made from fresh fruit juice and cachaça.

TO THE COAST

While Paulistanos think little of driving the three hours or more it can take to reach the Atlantic shore from the city, John and I were very happy that we opted to hire a driver for around $200 USD (a standard taxi is about $150, and surprisingly comfortable buses with reclining seats are under $50 per person). Amid the winding 2500 foot descent through the Serro do Mar mountain range to the sea, we were suddenly deluged by thick curtains of rain which continued steadily for twenty frightening minutes. Our driver slowed a bit, but confidently soldiered on with a determined smile on his face. John and I held white-knuckled hands.

Afternoon inundations like this are a common weather pattern here, just south of the Tropic of Capricorn. In fact, Ubatuba, which in the native Tupi languages meant “gathering of canoes,” is today nicknamed Uba-chuva (Chuva being Portugese for rain).

During our time along this golden coast, we came to appreciate the downpours, which came and went like clockwork, as a welcome break from the powerful sun. Cold showers, long naps, and cocktails on covered patios became part of our languorous daily rhythm.

The sun was already breaking back through the clouds as we arrived in the first of three beach towns we would leapfrog amongst in the coming days: Juquehy, Camburi, and Maresias.

Juquehy’s Hiu Hotel is just 500 yards from the beach, but a comfortable block and a half off the town’s main commercial road, Avenida Mae Bernarda, assuring an almost complete absence of traffic noise. There is no escaping the morning crow of roosters however; many of the locals keep chickens.

Just after the dawn cock’s call, or just before the sun sets at dusk, the three mile walk along Juquehy beach is a balm for the soul. The wide band of sand is as white and fine as sugar and the water astonishingly clear. Even standing waist deep, you can see your toes wiggle.

Sundown turns the gentle surf to liquid bronze and the sky a palette of pinks and oranges. Remember the scenes on those lovey-dovey Hallmark cards you made fun of as a kid? Well, you’re pretty much inside of one here, and its time to admit you were a pretty snotty kid.

Juquehy beach is much busier in the mid-day hours. Lounge chairs and umbrellas are rented by surfside bars, and holidaying Brazilians set up nets to play both conventional volleyball and the astonishing “foot-volley,” a hands-free version that takes advantage of its players’ well-honed soccer skills (as well as offering views of their well-honed abdominal muscles).

As Ilha (Photo by Jim Gladstone

Back at the Hiu for an afternoon break, we’d take a dip in the small courtyard pool then head up to the small rooftop sauna that no other guests ever seemed to discover.

For dinners, we headed to the compact village center where most restaurants offer both indoor and outdoor seating. Menus are largely similar, with a focus on fresh local seafood, simply prepared. Moist, mild white-fleshed daurade can be found on most menus in a variety of preparations ranging from simply grilled and served whole, to fileted and garnished with tropical fruit sauces or salsas.

One restaurant, Familia Oliveira is worth a visit for the monochromatic marvel that is their risotto de palmito, an ivory blend of arborio rice and tender fresh hearts of palm, subtly seasoned with onion and

parmesan. Simple and sensational.

Perhaps the swankiest epicurean experience along this stretch of shoreline can be found at the Hiu’s nearby sister property, the luxury 15-room Nau Royal on Camburi beach, about 8 miles north. Its YYE restaurant is an arrangement of cloth-sided white cabanas overlooking the ocean from a manicured palm garden punctuated with sapphire wading pools and upholstered conversation pits.

Nau Royal (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

While it’s open to the public for dinner as well, John and I were glad to have visited YYE for lunch, when the menu is the same, but the luxury of the grounds and the beach can be fully appreciated, a feast for the eyes nearly matched by Chef Artur Dornelle’s exquisitely plated dishes.

Technicolor cocktails were accompanied by an an adorably presented appetizer of crispy fried fresh anchovies served in a copper basket with a sidecar of tangy lime aioli. Cilantro-flecked whitefish ceviche was served with coconut milk in a glossy blue lacquered bowl.

Hearts of palm (as ubiquitous as cachaça in these parts) this time appeared in pappardelle-like ribbons, tossed with pink shrimp, diced apples, bias-cut snow pea strips and crispy bacon-flecked farofa (toasted cassava flour, a Brazilian staple). A pasta dish? A salad? A stunner!

Another few miles up the coast from Camburi, the town of Maresias serves as a starting point for some of the region’s most appealing nature expeditions. One morning, we joined about a dozen other travelers, mostly Brazilian, on a half-day guided boat tour of nearby islands.

On Montão de Trigo (which means “pile of wheat”) where the population hovers around 50, local entrepreneurs have built a ramshackle dock area with swaying, suspended walkways and diving platforms to encourage snorkelers to stay awhile and order some cold drinks and generous portions of fresh fried coxinha (croquettes filled with shredded chicken and creamy cheese), one of the region’s favorite snacks.

The snorkeling area is calm and easy to navigate, sheltered by a spit of seaworn bouldersthat look like giant rotting teeth. Silvery ovalsea bream, yellowstriped French angel fish, and skittering lobster were easy to spot.

There’s an altogether different sort of wildlife on Ilha Dos Gatos, which, acrawl with an estimated 750 feral cats (to be spotted safely from the shoreline). They’re alleged to be the offspring of pets once owned by members of the Rockefeller family who, in the early 20th century began to establish a South American getaway, which they later abandoned.

Ilha Dos Gatos near Maresias (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

On As Ilhas there are two beaches ideal for sunning and swimming, separated by a forested area. Hike a few yards away from the shoreline beneath leafy canopy and you’ll find a charming sort of speakeasy: a small family operated concession selling snacks and drinks to enjoy at small wooden tables in the shade of the trees, away from the beating sun. The eastern side of As Islas features impressive rock formations surrounding shallow spring-fed pools.

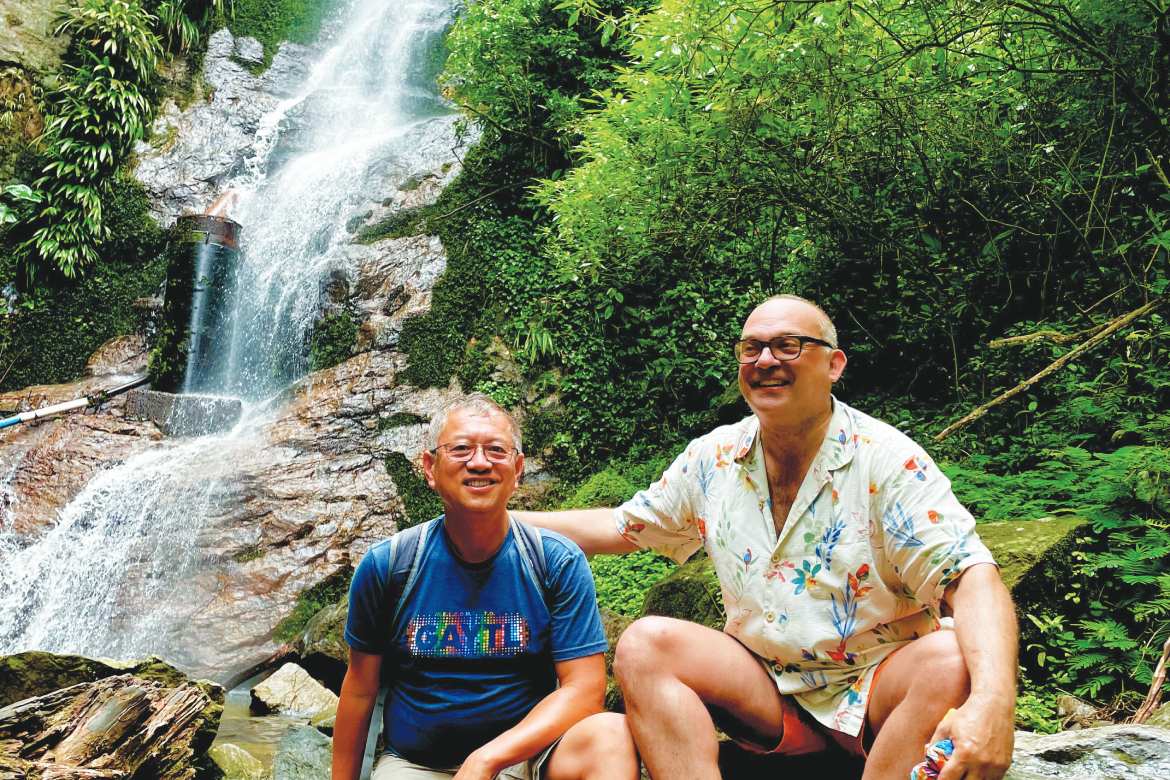

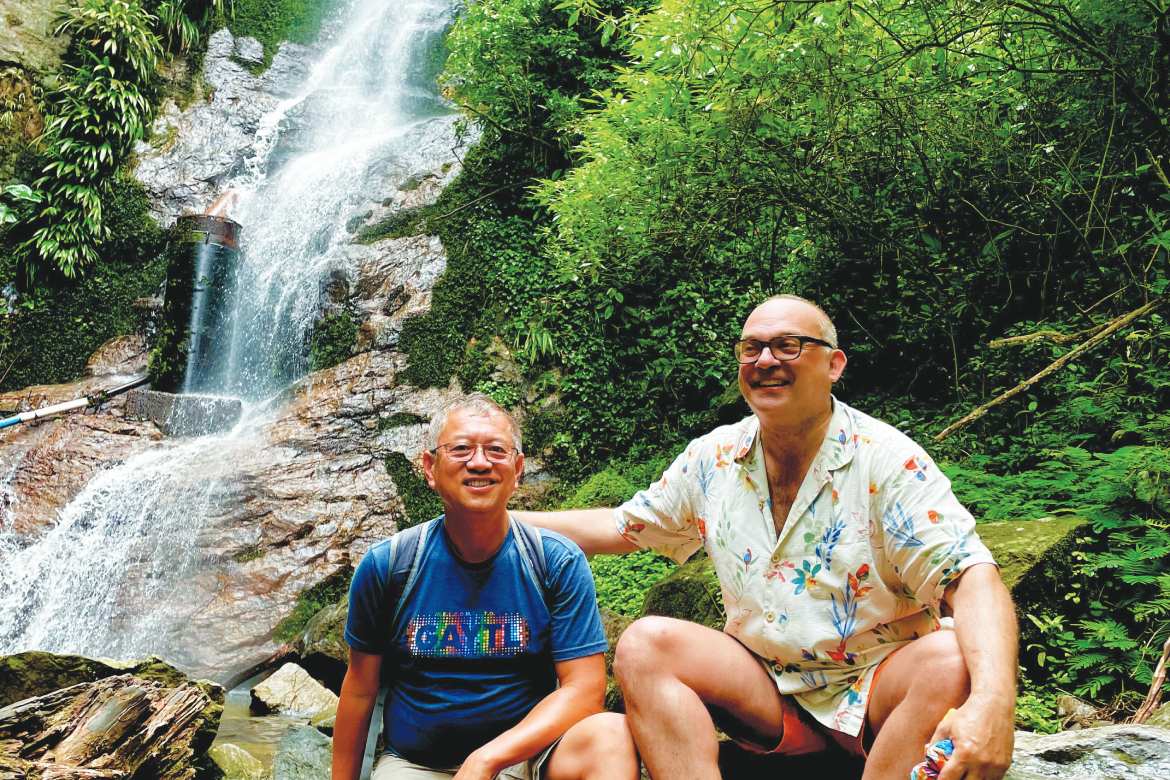

The following morning, the Maresias Tur company put us in the capable hands of a guide who called himself ‘Simpson’ and was amply tattooed with images of that yellow cartoon family. An expert in the flora and fauna of the Atlantic forest, he led us on hikes to two impressive waterfalls, the second of which was deep in the woods, where we’d never have discovered it on our own. As we stood by the bottom of the cascade, Simpson slipped his hand into the runoff and emerged with a tiny golden frog in his palm, no larger than a pinky fingernail.

John & Jim at Maresias Waterfall (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

Along our route, he pointed out several forgeable local plants, which we cautiously nibbled; spectacular bamboo groves (while most commonly associated with Asia, 137 different species of bamboo grow in Brazil); an abundance of orchids and other wild blooms; rainbow eucalyptus trees with peeling strata of multi-colored bark; and the amusingly shy mimosa pudica plant, whose narrow green leaves curled up defensively when we ran our fingers along their edges, then slowly, cautiously stretched out again.

Such aloofness never felt necessary for John and I as a gay couple on these excursions, nor at any of the hotels where we stayed. No desk clerks batted an eye when we checked into our king bed rooms, and we felt completely at ease asking tour guides to take photos of us with our arms around each others’ shoulders.

Despite the fact that nonchalance toward same-sex couples is fairly standard in Brazil’s big cities and popular beach towns, part of the added value provided by Marcelo and MH Tour is the assurance that they have personally vetted all of the accommodations and vendors to whom they send queer clients.

We loved our stay at the Maui Maresias, a beach block hotel and spa with bright white interiors and dark wooden decks shaded by pergolas hung thick with pale purple blooms. Public areas were enlivened by whimsical design touches including cocoon-like wicker chairs and a bar where the seats are suspended from the ceiling like playground swings: Inner child, meet adult beverages!

As Ilha (Photo by Jim Gladstone

On our final morning in Maresias, Simpson took us hiking once again, this time through a well-groomed nature preserve leading to a rugged little peninsula that juts out into the ocean for just short of a mile. From stone platforms along the steep embankments, fishermen cast long lines into the ocean below.

At the far end of our walk, we turned back toward shore and took in a panorama of two pristine beaches, Maresias and Pauba, each completely blocked from the other’s view by the natural barrier on which we stood.

FEELING THE SPIRIT

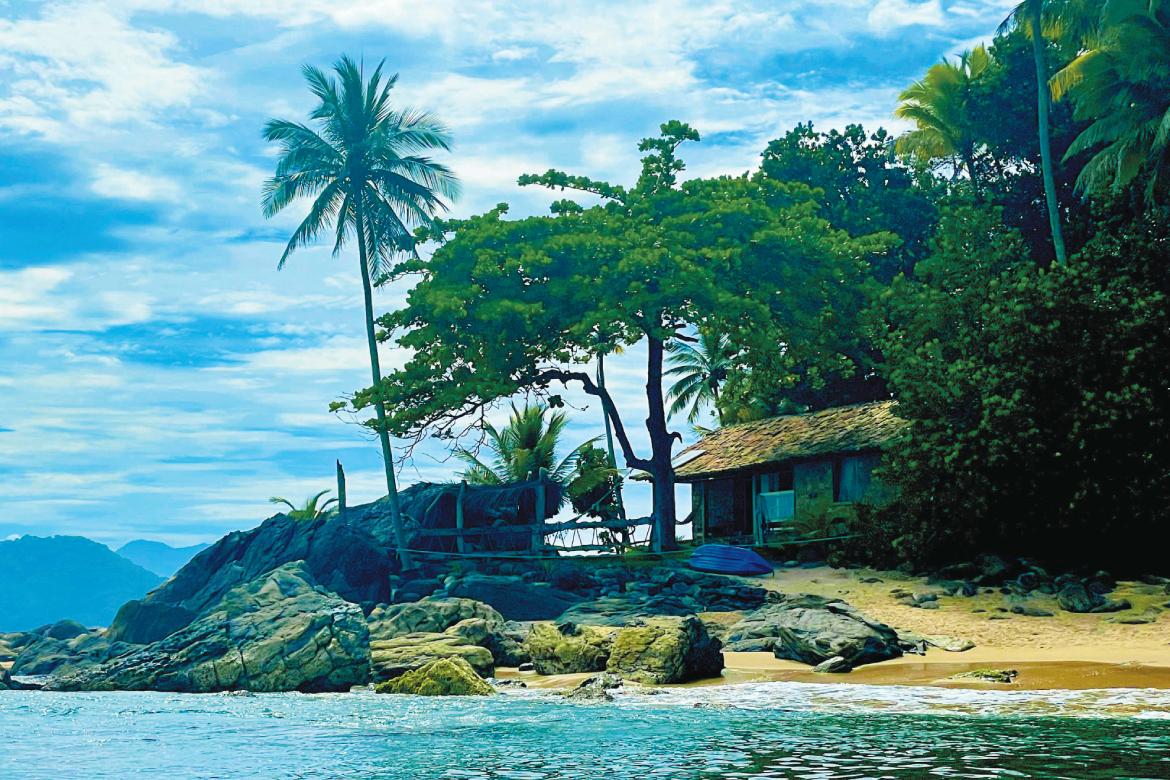

By this time, we’d already seen several beautiful islands and Ubatuba would bring us many more, but there is only one officially named Ilhabela (“beautiful island”).

Reached by a three and a half mile ferry trip that departs the small city of São Sebastião, less than an hour north of Maresias, the 135 square mile island, 85% of which is a UNESCO-protected rainforest, is a favored getaway for well-to-do Brazilian families; a sort of tropical Nantucket.

Small beach coves ring the island’s perimeter, and its central commercial area, called Vila, has dozens of al fresco restaurants, a surprising number of which specialize in pizza. A happier surprise is that many also feature bars with live music, from guitar-and-vocal duos to larger ensembles playing Tropicalia, the blend of traditional Brazilian music and jazz made famous worldwide by songwriters including Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil. The small, well-curated Waldemar Belisário Museum has evening hours on weekends, and the streets are lined with handicrafts vendors.

Street Vendor (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

But the reason we’d return to Ilhabela is the gay-owned and operated Elephant Guesthouse, a stunningly situated oasis on the island’s west side. It’s named for the shape of a massive black rocks that erupts from a deep green back lawn that rolls down to the sea from a shady porch.

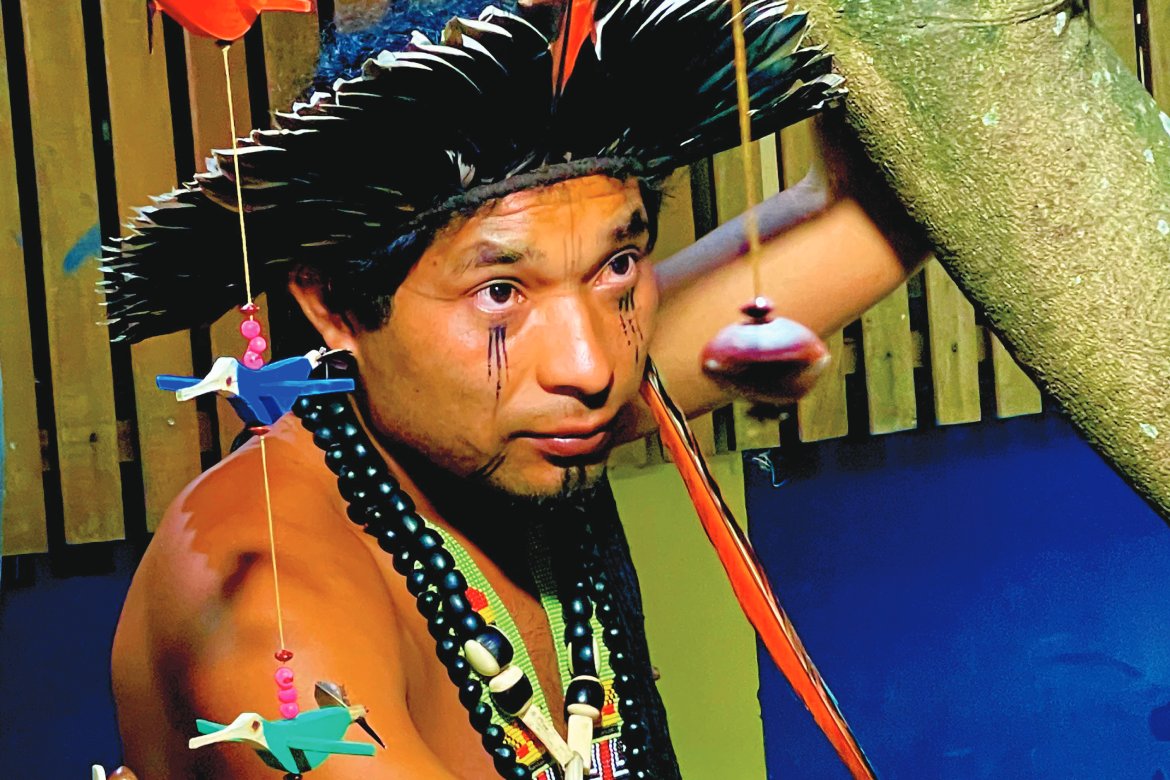

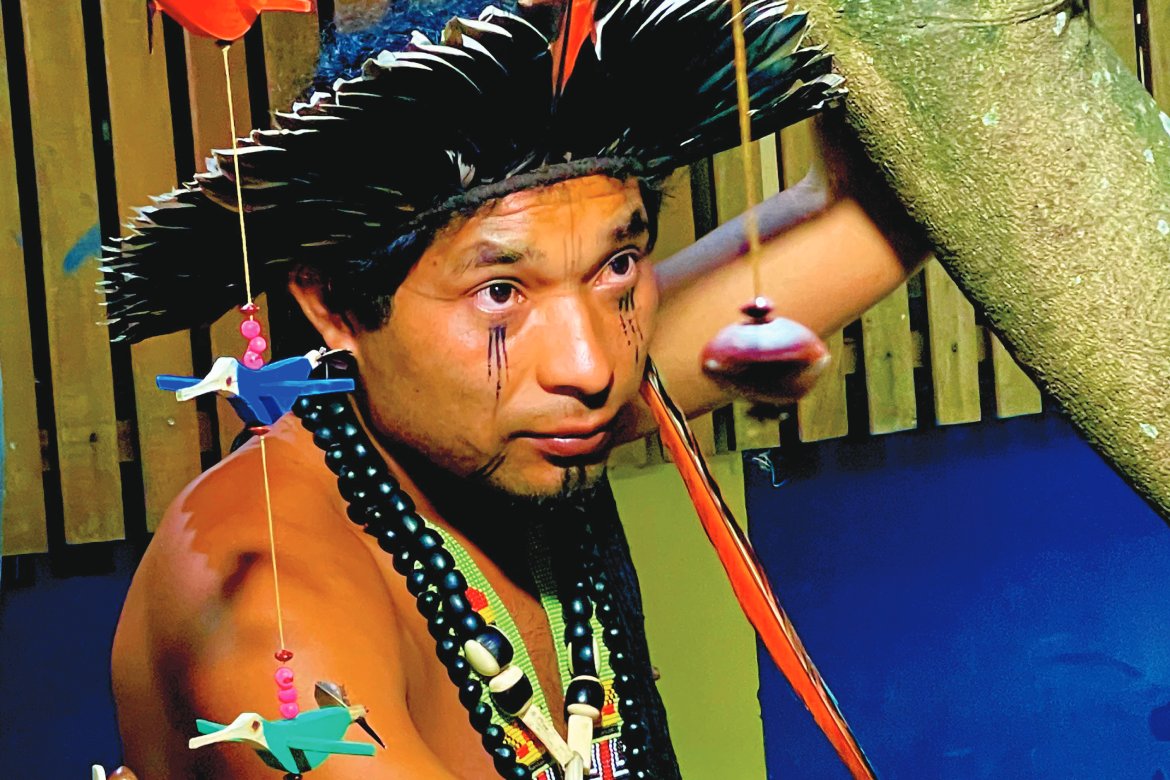

Unbeknownst to us, the date we arrived, February 2, is the annual holy day for Iemanjá, a goddess of the sea in the Afro-Brazilian religion called Candomblé.

A hybrid of West African and Catholic faiths, developed when 16th century slaves were forced into Catholicism, Candomblé is most prevalent in the Brazilian state of Bahia. The celebration of Iemanjá, however, has made its way to virtually every coastal area, and anyone is welcome to participate.

Elephant owner José Carlos dos Santo, who goes by Carlos, gathered his local friends and lucky guests on the inn’s back porch around a tabletop shrine containing small stone fish, female figurines, fresh fruit, palm fronds, and baskets piled with flowers.

While slightly disoriented to arrive just as this ceremony was about to get underway, John and I were quickly absorbed into the group, and gamely tried to sing along with a chant that Carlos led.

Moments later we found ourselves joining a procession, flower baskets in tow. We walked up the driveway, down the street, and onto a small beach where smiling bathers parted to let us pass through to the ocean’s edge. One by one, Carlos anointed group members’ heads with sweet scented oil and we stepped into the sea with flowers in our hands, setting the blossoms afloat, then submerging ourselves beneath the waves.

“Iemanja is a great tradition,” Carlos told us later, over bowls of feijoada, the traditional Brazilian pork and black bean stew. “I’ve studied many religions, but you do not have to be religious to celebrate. It is a

way to say thank you to the sea, to mother nature.”

For John and I, participating in the ritual not only helped us feel our connection to nature, it gave us a uniquely intimate experience of Brazilian culture that will always have a prominent place in our travel memories.

The ideal host, Carlos, an English-fluent civil engineer by training, is happy to engage in long discussions about Brazilian culture, but equally ready to slip into the background and give his guests a chance to take in the romantic environs.

The guest rooms are large, if basic, but because there are only six of them, the sprawling grounds never feel crowded, and that outdoor space, plus a deck and shared living room lounge full of comfortable colorfully upholstered furniture, is what makes the Elephant so special. (The entire compound can be bought out for about $800 per night).

Follow a stone walking path down the lawn toward a stand of palms, take a flight of wooden stairs and find yourself at a long private pier. Then climb down a short ladder into clear, shallow water, just about five feet deep close to shore. There are huge rocks to clamber up and sun on, and plenty of perches where you can comfortably sit submerged in warm water up to your shoulders.

As I sat alone, my swim trunks left behind at the ladder, I breathed deeply and felt as relaxed as I can ever remember. A small turtle climbed up on a rock beside me and two seabirds landed on another, just yards away. Thanks, Iemanja.

NÃO FALO INGLÊS

After a second night’s lazy stay at the Elephant, we were joined at the breakfast table by none other than Marcelo, travel agent extraordinaire. To our astonishment, he’d volunteered to drive five hours from São Paolo to accompany usto Ubatuba, about another two and a half hours north along the coast.

“You were so excited about visiting there, I thought I would like to join you!” This was a cheerful half-truth. My mental elevation of Ubatuba to Promised Land hadn’t only surprised Clovis of the IGLTA: John and I were Marcelo’s first foreign clients to specifically request a stay there. While the local beaches are indeed paradisiacal, Ubatuba is primarily popular among Brazilians.

Marcelo had no sense that the area would be any less hospitable to a gay couple than the rest of the laissez-faire Litoral Norte, but was concerned that we might struggle trying to communicate. In addition to checking out potential future business partners, Marcelo wanted to be on hand as a surreptitious translator.

He needn’t have worried. Between my well-honed charades skills and John’s dexterity with Google translate, we’d happily bumbled along for a week on our own already. The fact of the matter is that the majority of Brazilians we’d met anywhere outside of São Paulo, even those who worked in the hospitality business, spoke only very basic English.

Unless you have the funds and inclination to be cosseted in fully-guided five-star luxury, your enjoyment of exurban Brazil will somewhat depend on your comfort with playful, unhurried communication.

To me, this is part of the adventure, and part of the valuable humbling that comes in traveling abroad without a tour group. Having to fumble in a foreign tongue shrinks your ego, but ironically makes you feel pride in even your smallest successes.

Still, even for travelers accustomed to independently organizing their trips, working with a trusted multilingual travel agent can make ventures beyond Brazil’s city centers infinitely easier. Assistance in planning the overall itinerary, making reservations, arranging transportation from place to place, and addressing any urgencies along the way can be invaluable.

Indeed, while personally chaperoning us in Ubatuba was an exceptional occurrence, Marcelo explained that on a daily basis, throughout all of his clients’ trips, he and his team members call ahead to hotels, restaurants, and transit companies to confirm scheduled plans and iron out any wrinkles. One needn’t travel high end to have a seamless experience.

With six guest rooms, a shaded open-air bar and a postage stamp of a swimming pool perfect for post beach lolling, the

petite Casa Melville hotel in Ubatuba is a tucked away gem. Just two blocks off of the small town’s commercial strip, it’s surprisingly quiet and oriented toward the sea. Only a broad median of lawn with a public volleyball court (an eye candy shop from morning to night) stands between the front gate and a broad beach.

It’s also adjacent, through a door at the rear of the lobby, to a fantastic little surprise of a restaurant, Sushi Bistro, run by Japanese Paulistas who are at the top of their game. Huge platters of impeccably fresh fish are served nigiri, maki, and sashimi style at about 30% less than one would expect to pay in the U.S.

That said, while Brazil has the largest population of Japanese heritage outside Japan, Ubatuba also offers the opportunity to sample some definitively Brazilian seafood specialties, notably at Peixe com Banana, a restaurant that specializes in its eponymous dish: fish with bananas. This unexpected combination of ingredients (the bananas in question are not sweet but starchy, like plantains) is central to the cuisine of the caiçaras, natives of the southeastern Brazilian coast descended from a mix of indigenous, African and European people. They’re stewed in delicious, earthy broths of coconut milk and red palm oil with onions, mild peppers, and tomatoes.

Fish Plantain Stew (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

As we finished up a light breakfast on Casa Melville’s terrace our first morning, Marcelo received a call on his cell phone, then grinned broadly and gestured toward the surf.

A sleek white speedboat was idling just yards from the shore , arranged by Marcelo through Rota do Surf, one of Ubatuba’s highest rated pleasure cruise companies.

In addition to private rentals, it’s easy to join a small group of other travelers on regularly scheduled nautical excursions. And water taxis, which cost just a few dollars a ride, require no reservations and have regularly scheduled routes, are plentiful. You’ll find stations at major mainland beaches including Praia Felix and Praia Amado, which features an enormous tented restaurant and bar, festive with music and serving gargantuan grilled lobsters and doormat-sized flounder glazed in passionfruit juice.

Lobster Ubatuba (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

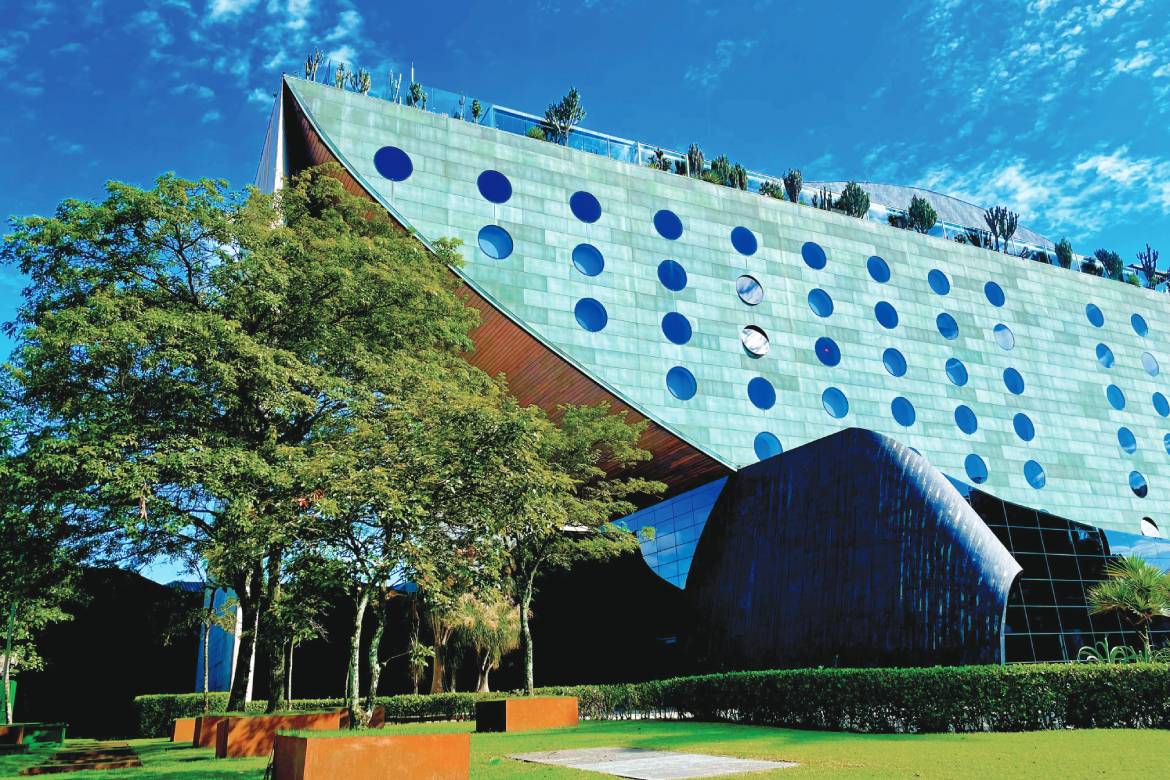

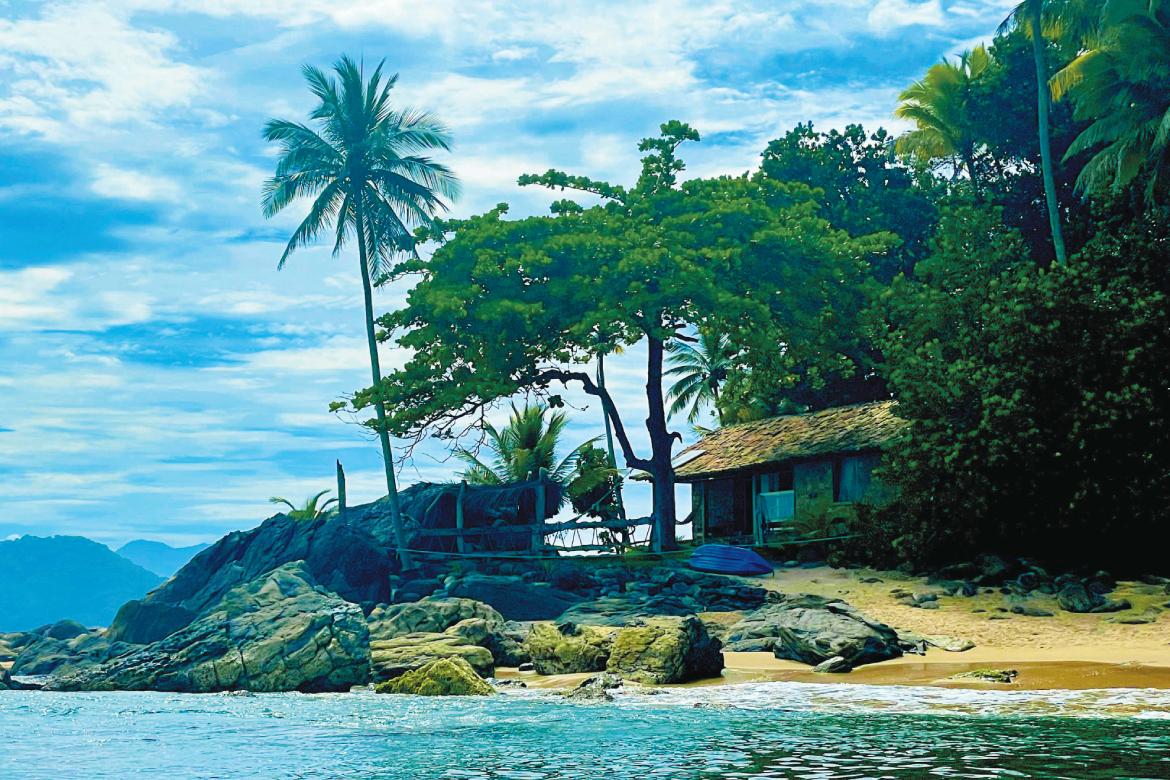

The most authentic part of Ubatuba is neither its mainland town center or biggest, most crowded beaches; it’s the spectacular scattering of small, irregularly shaped islands offshore. Zipping among them over the next two days offered dazzling views and happy disorientation. Where did we come from? What direction are we going in now? Can it get any more beautiful?

Ilha das Couves is among the most enchanting of Ubatuba’s ocean jewels, with two fine-grained beaches along the perimeter of lush, shaded for est. But this tiny paradise of just under three acres grew so popular among local beachgoers that its delicate eco-system was threatened.

In 2021, it came under the protection of the Såo Paolo state Forest Foundation. The result: It’s more alluring than ever. Limited to just 177 visitors at a time, in regulated daily blocks from 8-11 A.M., 11 A.M.-2 P.M. and 2-5 P.M., the beaches, which once resembled cans of suntanning sardines, now feel spacious and meditative.

Permits are required for boat operators to drop guests at a single landing where foundation rangers provide a brief orientation. From there, John and I took a short well-marked trail to the second more secluded beach, toting snorkel gear that was included in our boat fare.

In a cove of bathtub-warm turquoise water we swam only about 50 feet from the shore before spotting huge black rock formations through the transparent turquoise water. Among them, two giant sea turtles, each nearly four feet long and utterly undisturbed by we humans, grinning in silent delight and exchanging submarine thumbs up.

At the even more miniscule Isla dos Porcos, we swam ashore from our boat and had a crescent of sugary white sand entirely to ourselves. The public islet’s single private residence, a 9-bedroom beach house, available for rent, was empty at the time, allowing us to enjoy a half hour playing castaway trespassers.

Ilha Dos Porcos View From Mainland Ubatuba (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

“Now,” said Marcelo, as we climbed back aboard, “We will see the very smallest beach in Ubatuba.” Off we sped for a circumnavigation of Ilha Rachada, which is actually less an island than a massive peaked rock, rising from the ocean like a great gray iceberg humorously capped by an oasis of palm trees.

In circling, we saw that what atfirst appearsto be a single landmassis actually cleaved in two, with an alley-like channel of sand bisecting the entire width of about 120 feet. This “beach,” never more than a few feet wide, is flanked by soaring rock walls with ocean at either end. Seen in aerial photos, it’s clear why locals refer to this oddity as Asscrack Island.

One afternoon, as we motored from beach to beach, I saw an arc of silver flash alongside the boat. Then another, about 10 yards ahead. The captain slowed, then idled and we quickly realized that were in the midst of a pod of Atlantic spotted dolphins.

Leaping, whistling and literally surrounding us, these elegant, seemingly carefree creatures dazzled. I felt as if some unconscious wish I’d never articulated had nonetheless been heard and granted. It was one of those moments when travel blurs into transcendence.

Obrigado, one of the few Portugese words I’ve managed to memorize, is a simple “thank you.” It felt wildly insufficient when I dashed across Avenida Leovigildo Dias Viera to embrace my old acquaintance Felipe Abilio.

I’d tried to tap his expertise when first beginning to plan this trip that he’d inspired, but even after tracking him down online, our language barrier and his hectic schedule made it challenging to maintain communication. Once a São Paolo-based writer for Brazilian Vogue, he was now living back on his native turf, happily (but exhaustingly) beachcombing, island hopping and frantically video editing to generate a constant stream of clips and images (and eke out an income) by celebrating Ubatuba and the Litoral Norte on an array of social media channels.

After arriving in Brazil, I began texting him again, and finally, on this last night before heading homeward, had arranged a hasty reunion.

“I would never have done any of this if hadn’t run into you in Paris,” I explained over mango and coconut ice cream on the patio of Santin Gelato Artesanal, a sprawling indoor-outdoor Ubatuba institution.

And it was true. Felipe’s ebullient hometown pride had planted the seeds of this entire adventure, a hemisphere-crossing lark born from a few short video clips and the goofy music of the word Ubatuba.

“So, you liked?” he inquired, a confident grin already spreading across his face.