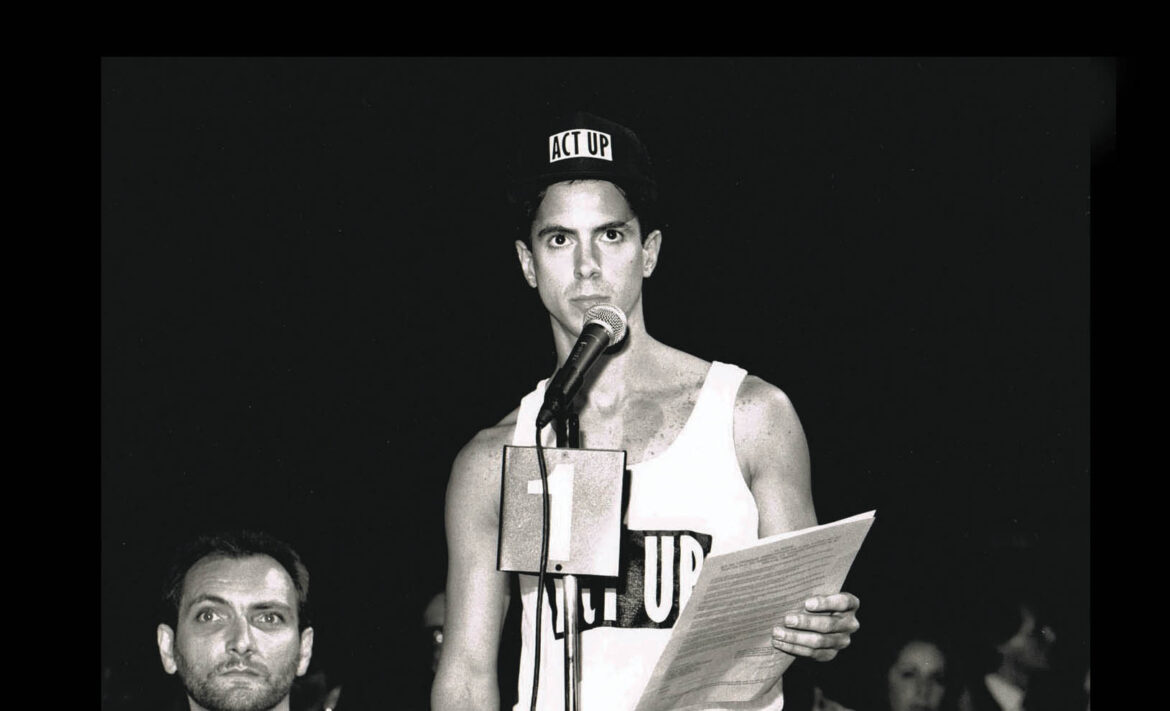

Peter Staley was the proverbial poster boy and the leading voice for ACT UP in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

He moved to New York City in 1983, taking full advantage of the mecca of gay life and sexual freedom, only to test positive for the AIDS virus in 1985. With his boyish, good looks, charm, and a fierce determination and commitment to find a cure or a vaccine for the AIDS virus, Staley, left his six-figure, Wall Street, bond trader job filled with homophobic, straight male co-workers, to pursue activism full time, joining ACT UP in 1987.

He spent the following years attending ACT UP meetings on Monday nights, planning and strategizing actions to pressure major, pharmaceutical companies to lower the astronomical price of AZT, a highly toxic and not very effective drug, but the only one available at the time, shaming the U.S. government and the president to recognize AIDS and to take action, and relentlessly pushing U.S. health agencies to fast-track approval of new drugs to fight the virus. Their unorthodox but highly effective method of executing public actions and demonstrations, which received unprecedented media attention, became the model for many latter-day organizations.

After much infighting and turmoil in ACT UP, Staley quit the organization in 1992, and formed a new group, TAG, Treatment Action Group with other frustrated ACT UP members. TAG dealt hands-on with drug trials and research, and lobbied government health institutions such as the FDA and NIH, working closely, but sometimes sparring with, Anthony Fauci.

In October of 2021, Staley’s memoir, Never Silent: ACT UP and My Life in Activism, was published. The tell all book (but not in a gossipy, dish the dirt way), is a candid, no holds bar account of Staley’s highs and lows of his ACT UP days and the unpredictable path his life took after he semi-retired from AIDS activism in the late-1990s, including a short-lived but serious crystal meth addiction in the early 2000s, and becoming a consultant on a major Hollywood film about AIDS in 2013.

Where were you born and where did you grow up?

I was born in Sacramento, California. My dad worked as a plant manager for Procter & Gamble, and we moved around the country every few years until finally settling outside of Philadelphia. From the age of eight, I grew up in Berwyn, Pennsylvania.

Please describe what gay life in New York was like when you moved there in the early 1980s?

I arrived in New York fresh out of college in 1983, but stayed deeply closeted because of my job on Wall Street, trading U.S. Government bonds for JPMorgan. The outward homophobia on the bond trading floor was intense, like a high school locker room run by dumb jocks. But I was able to find refuge every weekend at various gay bars in the West and East Village neighborhoods. My favorite was Boy Bar on East 8th Street, and St. Mark’s Baths was just across the street. Even though we were entering year three of the AIDS epidemic, I heard very little talk of it that summer at the bars or bathhouse. Twentysomethings like me largely discounted the threat. We didn’t know anyone who had it—yet.

Who or what inspired you to write your memoir?

The reaction to How to Survive a Plague planted major seeds for the memoir. I was overwhelmed with private messages over social media from young people inspired by that history. I stayed in touch with many of them, as they entered activism or a career in public health. It proved to me that personal narratives can really inspire folks. And then friends like Anderson Cooper kept pushing me to tell my own story, my way, as an additional way to inspire folks. I had a lifetime hatred of writing, but decided to challenge myself after these various inspirations built up over time.

How long did it take you to write, and what was the process like?

It took me three years, and I hated every minute of it! But I finally did it, and I’m very proud of how it came out. The COVID lockdown helped—I ran out of excuses for not finding time for knuckling down and writing something each day.

Seize Control of the FDA, ACT UP demonstration, Oct 11, 1989 (Photo Donna Binder)

Which ACTUP action had the most impact and received the most media coverage?

“Seize Control of the FDA,” which took place on October 11, 1988. It was our national coming out as a movement, with all the new ACT UP chapters coming together to surround the FDA’s headquarters in Rockville, Maryland. All three TV networks had us as their lead story that night, and every national newspaper covered it too. That was the night I went on CNN’s Crossfire show and tangled with Pat Buchanan, one of our nation’s right-wing firebrands. Within one year, the FDA caved to most of our demands, especially our call for a Parallel Track program that would allow patients to access drugs outside their final clinical trials. By the end of 1989, tens of thousands of patients were accessing the second AIDS drug being researched after AZT, called ddI. And we became America’s movement de jour, quickly guilt-tripping the public into supporting more tax dollars for AIDS research.

Was there an action that was more meaningful to you personally or that you are most proud of?

I open the memoir with the action I led invading the trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange, protesting the price of AZT. I had left my job on Wall Street the year before, and had a wonderful catharsis of staring down those homophobic traders as we made international news. The company lowered the price three days later.

Even when the AIDS crisis was at its peak and the actions were so urgent and serious, there was a little bit of humor and perhaps irony, especially the Jesse Helms action. Was it intentional?

Not only was it intentional, but it was essential. With all the death and dying, we would have crumbled into little balls if we hadn’t lived life to its fullest during those years, with lots of dark humor. We were taking over the downtown dance clubs every weekend and had plenty of sex. To paraphrase Charles Dickens, it was the worst of times, but also the best of times. All of us who survived feel scarred by the experience, but also feel they were the best years of our lives—a very surreal experience. The best AIDS film of all time, BPM, a fictionalized narrative based on the early years of ACT UP Paris, captured it perfectly.

Arrest at Astra Pharmaceuticals in Westborough, MA, June 15, 1989 (Photo by William Walker)

At a certain point you were the main spokesperson for ACTUP in the media. Did the pressure ever get to you that the voice of the organization rested on your shoulders?

There were a few of us, but yes, I got a lot of media attention during our most impactful years. Being a spokesperson for a movement that bills itself as leaderless is a tricky thing. Do it badly, and you’ll squander a major opportunity for the movement, and get skewered within the group. Do it well, and you’ll be asked to do it again and again, and then you’re resented for it, especially if you enjoyed it like I did. It put a bullseye on my back once the infighting broke out within ACT UP. Given my age at the time, I didn’t always handle that pressure with the maturity I have now. Self-awareness comes in handy during activism and is the key to personal growth.

You wrote in the book that in the early 1990s, there was a lot of infighting in ACTUP and fierce arguments about the core purpose of the organization, so much so that you left to start another group. Please tell us about the group and what you accomplished.

TAG, the Treatment Action Group, is still going strong to this day. I was its founding director during its first five years, and it quickly became the most influential HIV treatment advocacy organization in the country. We quickly made waves by getting Congress and President Clinton to pass an NIH reauthorization that included a powerful Office of AIDS Research. Tony Fauci fought us tooth and nail, not wanting this new office to usurp his authority, but he was no match for the coalition work we led in that fight. TAG was also crucial in crafting the clinical trials for protease inhibitors, leading to the breakthrough drug cocktails that changed HIV/AIDS from a death sentence into a manageable disease.

Another thing you wrote about is the rampant sexual encounters that you and many of the other members were having with each other. Was it just because it was so accessible and easy, or do you think there was something else behind it?

Well, a group with hundreds of young gay guys and lesbians working non-stop will only accentuate our very human needs. Sex was an essential release. It was also political. ACT UP was the most sex-positive movement in history. We very intentionally pushed back against society’s stigma that gay men, in the face of AIDS,, should stop having sex, and worse, be quarantined. We said, “fuck that.” The science was clear, condoms worked. We firmly believed that safe-sex was safe, so let’s have lots of it. In fact, it became politically incorrect to avoid sex with HIV positive guys. And let’s just say I took full advantage of that.

What was the feedback from the book, and were there surprising reactions?

I’m getting wonderful notes from younger queer folk who find inspiration from this history, which is really our history. They realize they can add to it. Beyond that, I’m thrilled folks find it to be a good read (see its Amazon score). I still hate writing, but I had great stories to tell, and used my own story-telling voice to piece together a page-turner. It’s not your standard AIDS narrative.

Are you resentful that the U.S. government came up with a vaccine for COVID within 9 months and there’s still isn’t an AIDS vaccine or cure after more than 40 years?

Not at all. They’re apples and oranges. SARS-COV-2 is a fairly simple virus to construct a vaccine against. HIV is considered the hardest in history. Why? Because it’s sole purpose is attacking and destroying your immune system. Most other viruses attack other types of cells in your body. With HIV, scientists have to figure out how to prime an immune response that blocks a direct attack against that response. Billions and billions of dollars have been spent trying to figure out how to do this, and we’re not there yet, but It hasn’t been for lack of trying.

Does the COVID vaccine give you hope that a cure or vaccine for AIDS will become a reality in the near future?

Some. It’s the first vaccine using an mRNA platform technology, and now they are trying that against HIV. The platform is definitely more flexible to work with, so hopefully that will speed up an answer for an HIV vaccine.

What do you think are the most important issues the LGBTQ+ community is facing today?

After some quick advances in most of the wealthier democracies around the world, we’re now being hit by a significant backlash. In the U.S., it’s mostly against the trans members of our community. Overseas, what just happened in Uganda, with full criminalization of everything LGBTQ, is horrifying. We’ve got plenty on our plate. I hope we get back to basics of fighting against discriminatory laws and policies. I get in trouble for saying this, but we’ve spent too much time on policing language, which rubs up against basic human nature. No one likes being told what they can or cannot say. But everyone understands that we all deserve basic rights.

What was the response to the book from the current gay generation who read it, and what is your consensus of the current gay generation about AIDS?

Younger queers are really blown away by this history, what I think is the queer movement’s greatest moment, especially when they first start learning about it. It’s very cool that my book is sometimes their introduction to that. They usually want to see and read more about it once something hooks them in. I was asked to join a new HIV prevention group in 2018 called PrEP4All, launched mostly by HIV negative gay men in their twenties. These younger activists are doing extraordinary work. With all that’s going wrong in the world these days, they are the only thing giving me hope.

You May Also Be Interested In

Alan Cumming Talks