How Eugene Hernandez, who was raised in a typical, middle class family in southern California in the late 1970s with a cultural diet mostly consisting of sitcoms, Disney, and cartoons, became one of the most significant figures in the film world is a fascinating and eye-opening story.

Staying close to home after graduating high school, Hernandez moved to Hollywood, the movie capital of the world. While attending UCLA, he discovered a new world of films that included underground directors, outsiders, and gay characters, which he hadn’t seen before. Eventually Hernandez moved to New York City, a place that took his newborn love for the art of cinema “seriously” and also where his career in film started and flourished.

His early New York years were spent working in television, but he pursued his interest in film by attending film festivals and screenings in his spare time, which also gave him access to a community of like-minded film aficionados. Hernandez and a small group of his new friends developed Indiewire in 1996, a new website devoted to disseminating pertinent information about indie films. The little website that could, morphed into a full time career and business for Hernandez and two other partners for 15 years.

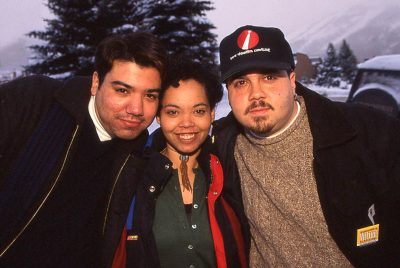

Hernandez with Indiewire co-founders Cheri Barner and Mark Rabinowitz at the 1996 Sundance Film Festival (Photo by Randall Michaelson)

In 2010 Hernandez was pleasantly surprised when the Film Society of Lincoln Center offered him a job to update the 40 year plus institution with his knowledge of new technology and digital film. They valued his contribution over the years, and he was recently rewarded with being promoted to the top position within the organization. Hernandez’s stature in the film world positioned him to recognize and advance the growth of LGBTQ cinema and other under-represented groups in film.

Where were you born and where did you grow up?

I’ve lived in New York for exactly half of my life now, but I absolutely consider myself a Californian! I was born and grew up in a small Southern California town called Indio, it’s fairly close to Palm Springs. Much of my family is from that area of California’s low desert, where my grandparents settled after immigrating from Mexico.

What was the first movie you ever saw and what impression did it make on you? What other films made an impact when you were growing up?

It may sound a bit surprising given my field of work, but I didn’t grow up watching all that many movies as a kid, beyond Disney flicks, and the Star Wars saga. However, I did have a particularly memorable night when my parents took me with them to see Dog Day Afternoon at our local drive-in. To be honest, I don’t think much of it stuck with me, beyond the title and the fact that it was R rated (I was still only 7 years old at the time). I feel like I was shaped more by TV as a kid. I Love Lucy reruns, The Carol Burnett Show, and lots and lots of Bugs Bunny cartoons were my faves. Even in high school, I was way more focused on sitcoms, news programs, and TV specials than I was into movies.

My passion for movies began at UCLA. I started watching everything, new and old, in local cinemas, at the UCLA archive, or on a VCR with friends. The video store was a place of discovery for me. I was introduced to John Waters and Pedro Almodovar movies, both were like nothing I’d ever seen before: low budget, shocking, outrageous, and hilarious. And especially, I connected with American indie films that were similarly modest of budget but full of bold ideas, stories I’d never seen on screen, and people I had never experienced in my life.

I got involved with the student-run Campus Events Commission in the late 80s and started curating retrospective screenings, sneak previews with Hollywood filmmakers and talent, and other special events multiple nights each week. I did that for four years and developed a taste for offbeat, indie, and older movies. Paris is Burning, Spike Lee movies, Robert Townsend’s Hollywood Shuffle, and early Todd Haynes films clicked with me, but so did Hollywood classics Singing In The Rain, Sunset Blvd, and lots of Hitchcock films that I watched in film classes.

Later, when I moved to New York in the mid-90s (I was working at ABC-TV in LA and transferred to their East Coast HQ in the mid-90s), I would more meaningfully embrace foreign films.

In NYC I didn’t know many people. but immediately found a home watching lots of movies at the indie arthouse Angelika Film Center downtown and the Film Society of Lincoln Center (since rebranded as Film at Lincoln Center) uptown, and of course each fall at the New York Film Festival.

You started Indiewire with some associates in 1996 by doing daily email blasts. It eventually grew into the go-to site for the independent film industry. Please tell us how the idea came to you, what you wanted to achieve, and about the first few years of the site.

Indiewire grew from a shared passion for indie films and the search that a small group of us had for connection in the independent film community twenty-five years ago. I was working at ABC-TV in LA and New York, but was nurturing my interest in movies after hours. In ‘93, I took my vacation at the Sundance Film Festival, a place that I’d read was the proving ground for indie movies and directors. Sundance was a place of discovery for American independent cinema, especially new movies by women, people of color, and LGBT filmmakers (the New Queer Cinema movement), and that drew me in. I saved money to travel there each January and started writing as a freelance journalist to get into screenings and parties.

In the early days of Indiewire we started tracking Sundance as a real-time event, watching the first screenings of movies by up and coming filmmakers, writing up dispatches that night, and posting coverage online a few hours later. We also reported on the biz deals and snapped casual photos at parties. We even created a low-fi print daily that we Xeroxed at a local store and then slipped under the doors of attendees’ hotel rooms, or passed out to folks as they were waiting in line for screenings.

Indiewire grew organically from my UCLA and Sundance friendships, even though I’d never started a business. A small group of us simply shared a love of indie film, the opinion that marginalized movies and people needed a spotlight, and a commitment to building some sort of platform (an email newsletter, an early website, and organizing occasional events) to showcase films and filmmakers that might otherwise be overlooked by Hollywood and the mainstream media.

That was Indiewire. A daily online publication with news, reviews, interviews, film festival dispatches, inside info, party coverage, photos, and profiles of the people making, starring in, buying, selling, promoting, and who were passionate about indie film. We aimed to be the Daily Variety for the indie film community (its film makers, industry, and fans).

I spent 15 years leading, building, and ultimately selling the company. Every week, it was a challenge steadily growing a readership while trying to gain credibility, learning how to develop a business model, managing a budget, and sustaining a small company, and remaining committed to independent, marginalized artists and the spirit of discovery. We survived dot com busts and economic challenges to keep Indiewire alive, and this year it will celebrate its 25th anniversary (it’s now owned by Jay Penske and a sister publication to Variety).

Paul Weitz, Lily Tomlin, and Eugene Hernandez in 2015 (Photo by Julie Cunnah)

In 2010, you had a life-changing career moment when you left your longtime position as one of the founders of Indiewire for a position at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. Did the job offer come as a surprise, and what was the transition like?

I wasn’t looking for a new job when the folks at Lincoln Center reached out in the summer of 2010. They were grappling with how to evolve their 40-year-old analog arts organization and sought my guidance as a friend and fan of their work. Film at Lincoln Center’s movie theater was (and still is) my neighborhood cinema, and that organization, especially its prestigious New York Film Festival, shaped my taste in movies more than any other. So, I was thrilled when Lincoln Center leadership reached out.

The organization was building two more movie theaters on the Lincoln Center campus ten years ago and our occasional conversations about how digital tools and technology could play a role in their upcoming expansion led to their board and executives inviting me to create a new role on the senior leadership team.

Quite frankly, the transition was challenging at first. I’d had just two jobs in 20 years, and at Indiewire I worked with just a few close friends for a really long time. At Lincoln Center I was at the leading arts campus in the country alongside a huge staff, navigating a big budget with large annual fundraising goals, and an organization that was entering a period of some big changes. Over time I found my footing, working with the team to develop a suite of new programs aimed at nurturing and supporting women and people of color as artists and emerging professionals in the film community and cultivating new audiences.

When you started working at Lincoln Center, did you see it as an opportunity to further advance gay films and filmmakers?

Absolutely. Being gay, I feel that responsibility and commitment deeply. Since the earliest days of what I can now define as my career I’ve explored LGBTQ artists and audiences. I didn’t fully realize it at the time, but I’ve always been drawn to finding and nurturing art and artists who are, for whatever reason, on the outside or are marginalized.

I see art and media as a way to both connect with worlds outside of our own, or to be challenged to dig deeper in our own lives. Even as mainstream media embraces a wider array of stories today, queer writers and directors, female filmmakers, and artists of color face a much tougher time, not just finding a way into the industry, but building and sustaining a career. So I’m still focusing on acknowledging, addressing and tackling those inequities in my daily work.

Lesli Klainberg, Barry Jenkins, and Eugene Hernandez at the If Beale Street Could Talk NYFF56 premiere at the Apollo Theater. (Photo by David Godlis)

Another recent milestone in your career was being named the director of the New York Film Festival in February 2020. First of all, a big congratulations for this well-deserved honor. What do you want to accomplish in this new role?

Thank you. It was a humbling honor to be named just the fourth person to lead this 58-year-old New York Film Festival, an institution that is one of the leading events of its kind in the entire world. As long as I am in this role, I want to respect and continue the tradition and legacy of this beloved event, but also lead it into a new chapter by bringing a broader range of voices into the process of finding and inviting films and filmmakers to the Festival. This is about expansion. In this time of fundamental change in our country and in our culture, I want to continue to see this as an opportunity to find new ways to connect that art with a wider array of audiences.

2020, to say the least, was challenging for the movie industry and film festivals. The New York Film Festival was presented online instead of having its usual screenings. What was that experience like, and did it provide new possibilities for the festival? Will the festival continue with online programming in the future, even when screenings go live in theaters again?

Reconceiving, curating, and producing this latest New York Film Festival was frankly the toughest challenge I’ve faced in my more than thirty-year career. Embarking on the role before the pandemic I had ideas about how to refocus NYFF with my colleagues, but 2020 was both devastating and awakening for so many people, non-profit organizations, artists, and in many aspects of our society. If we can sustain our organization and programs beyond the ongoing obstacles we face in the wake of this pandemic, we have a chance to rethink and better focus our work, as well as engage new and existing audiences in different ways.

Even though 2020 was the 58th edition of the New York Film Festival, in many ways it was the first. The Festival happened entirely outside of its Upper West Side Manhattan Lincoln Center home for the very first time, taking place in drive-ins around the city and on a new national streaming platform. By doing this, we were able to connect with an entirely new audience of moviegoers in all 50 states and all the territories of our country. We hosted talks and events for a larger worldwide audience than ever before. There’s no question that we should continue to present a Festival in this new hybrid way and introduce its annual selection to new audiences in new ways.

NYFF58 Interview with Pedro Almodovar and Tilda Swinton

Another recent, significant alteration in the film industry has been the way people view films. Netflix, streaming, new technology for home theaters, films being released in theaters and on streaming platforms at the same time, have impinged on the traditional viewing of movies in a theater. How do you think this will play out in the upcoming years?

I’ve been thinking a lot about how I didn’t find my passion for movies until college, but today there’s so much available to anyone at the click of a button. The chance to introduce (or more deeply connect) audiences to cinema right now is my focus.

At Film at Lincoln Center we have an opportunity to play a fundamental role in that path of discovery of the art and craft of film. And the good news is that audience behavior was shifting even before the pandemic. We all discover and watch movies in all-new ways today, curating our playlist of movies via Netflix, Hulu, Apple, Criterion (and many other platforms). And movie theaters are a way for us to watch movies together. We’ll still do so after the pandemic, but moviegoers have more and more film choices available, and more ways to watch movies how and when they want to.

Film at Lincoln Center struggled to evolve ten years ago, but in that decade the organization has invested in programs, platforms, and people to meet audiences where they want to watch and talk about movies. In the coming years, I think the wisest companies and organizations in the film industry will evolve audiences by creating new ways of curating work, cultivating artists, and connecting with audiences.

Sofia Coppola and Eugene Hernandez in 2017 (Photo by Mettie Ostrowski)

What person in film, that you never met before, living or dead, would you want to invite to dinner?

The first name that comes to mind is Amos Vogel, a founder of the New York Film Festival who earlier in his career, back in the 1940s, started screening indie, underground, and avant-garde movies for small audiences downtown before he was invited uptown to Lincoln Center to curate and present films for even wider audiences. “The man was a giant,” Martin Scorsese praised when Amos passed almost nine years ago, “if you’re looking for the origins of film culture in America, look no further than Amos Vogel. I’d love to pick his brain and get to know him better

Are there any particular new trends in film or filmmaking techniques you’ve noticed in recent years? And if the answer is yes, are they positive or negative, or perhaps both?

I can’t say that I see trends per se, but at the most recent New York Film Festival, I noticed a number of films resonating in a particular way. I viewed Chloe Zhao’s Nomadland, the story of a woman who isolates herself in the wake of tragedy, in my small New York City apartment. It touched me in a profound way during the pandemic. I watched three new films by Steven McQueen: Lovers Rock, Mangrove, and Red, White, and Blue, each about the black community in McQueen’s England. These films resonated during the summer of the Black Lives Matter uprising for justice and equality. Steve McQueen dedicated these new films in his Small Axe series to the late George Floyd in the wake of Floyd’s murder at the hands of the police. In these specific films I see artists using their art to illuminate the moments we are living through right now.

You’ve traveled around the world to countless film festivals for over 25 years. What are some of the unforgettable events and moments you experienced?

I began traveling each year to the Sundance fest in the early 90s, Berlin a few years later, Amsterdam’s documentary festival in the late 90s, and then the Cannes festival in the early 2000s (and so many others). I’ve been thinking a lot recently, during this year of a pause in travel, about the memories I have visiting these festivals over the years because for me those have been the places of true discovery of films, artists, people, and cultures that have fueled my own work over more than three decades.

The unforgettable moments are the countless films and filmmakers I connected with at those fests: Pedro Almodovar, Radha Blank, Ryan Coogler, Ava DuVernay, Eliza Hittman, John Cameron Mitchell, Tilda Swinton, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Wong Kar-Wai, Agnes Varda, and so many, many more. I can’t want to get back to it, virtually for now and in-person again soon.