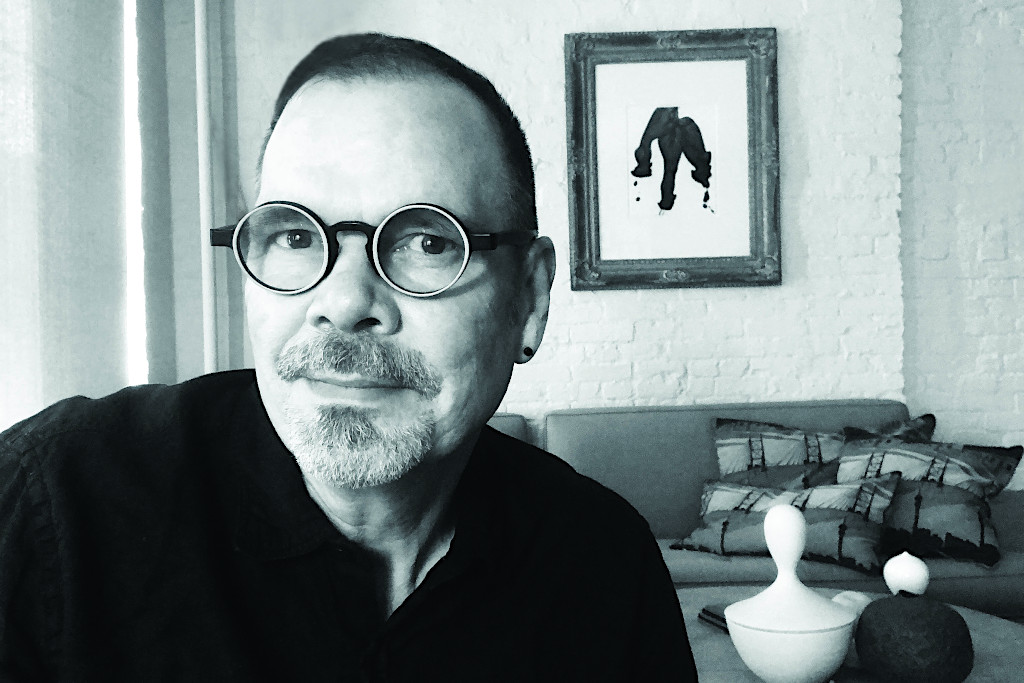

In 2012, David France’s stunning directorial debut, How To Survive a Plague, a documentary about the AIDS crisis in America, won accolades and premiered at the Sundance Film Festival; and it went onto be nominated for an Oscar.

David France first made his mark in the early 1980s writing about queer issues, and he was at the forefront of the AIDS epidemic writing for alternative gay publications. Throughout the next 30 years, he won numerous literary and journalism prizes for his hard hitting, investigative journalism published in prestigious publications such as The New York Times Magazine, Glamour, Rolling Stone, The New Yorker, POZ, and Newsweek.

He also wrote three bestselling books: Our Fathers, which was a detailed exposé about the Catholic sexual abuse scandal in the U.S.; The Confession, a New York Times bestseller, which he co-wrote with Jim McGreevey, the former New Jersey governor who hid in the closet while rising to political fame; and How To Survive a Plague, called “the definitive book on AIDS activism,” it also won the Stonewall Book Award.

In 2012, France’s stunning directorial debut, How To Survive a Plague, a documentary about the AIDS crisis in America, won accolades and premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. It went on to be nominated for an Oscar for Best Documentary Feature, and won a Directors Guild Award, an Independent Spirit Film Award, two Emmys, the Peabody Award, and a GLAAD Award.

His next film, The Death and Life of Marcia P. Johnson, was an original Netflix documentary released in 2017. It is about the amazing life of the transgender LGBTQ activist from the late 1960s until the 1990s, when she died under suspicious circumstances. The film won numerous awards including the Outfest Freedom Award.

France’s latest film, Welcome to Chechnya (released in 2020) is a searing and disturbing documentary about the persecution of gay men and lesbians in Chechnya, and how they perilously tried to escape violence and death in their own country. The film won a special jury award for documentary editing at the Sundance Film Festival.

Where were you born and where did you grow up?

Where were you born and where did you grow up?

I was born in a small New York State village called Suffern, a typical “bedroom community” just about an hour away from New York City. I lived in a fairly rural setting, our home was deep in the woods. When I was eleven, my father got a job in Michigan and moved the family there. I lived in Michigan until graduating college.

When did you know you were gay and how old were you when you came out?

I was probably aware of my queerness all along. In 4th grade, I fell in love with another boy, though I didn’t know what to call it. Things came into clearer focus after landing in Michigan, where I stood out for my fastidious fashion sense and my shoulder-length hair. I flew beneath no one’s gaydar! Very soon after starting school there, I was called a faggot for the first time. I had no idea what the word meant, but somehow I deeply understood that it accurately described me.

Did you study journalism in college and was that what you always wanted to do?

In university, I studied political theory. I volunteered for the student newspaper, called The Index, producing some of the most error-filled stories in its long history. So, I decided to go into academia and philosophy, enrolling in a PhD program at The New School.

You moved to New York from Kalamazoo in 1981 at the age 22. What were your expectations of New York? Did you think you would have more freedom to be out in New York?

I did expect freedoms, and was able to find them, even though I was a rather odd kid by New York standards. By the time I landed in New York I had abandoned my fancy clothes in favor of thrift-shop finds and, in fact, I had begun to eschew shoes, for a reason I can no longer remember. I enjoyed myself thoroughly. And I committed myself to the movement, such as it was at the time: I joined the Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee to help plan the pride march, and was a member of Lavender Left, a coalition of left-wing and radical queer groups and individuals. But my favorite fun from then was when Craig Rodwell offered me a job at the cash register of Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, which was an intellectual hub of queer New York.

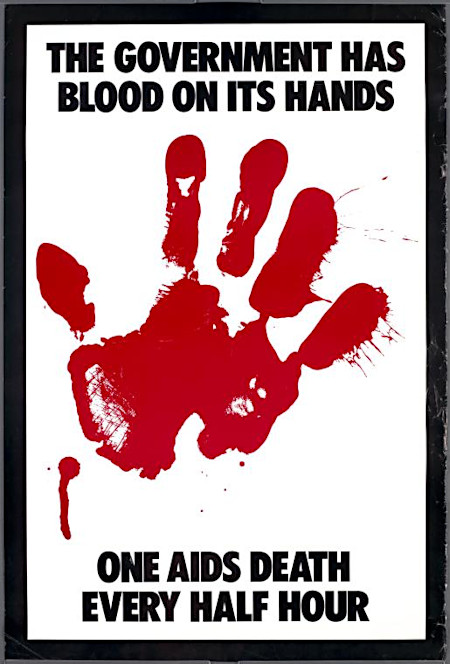

Shortly after you moved to New York, AIDS, before it was named that, was starting to infect gay men at an alarming rate. What was you first reaction when you learned what was going on and what was the content of the first pieces you wrote?

The first article about the mysterious “homosexual” disease appeared in The New York Times just a couple weeks after I arrived in town. I dismissed it entirely. To me it read like a gleeful warning shot, another way to present us as odd and diseased. I started paying more attention to it the following year, 1982, and wrote my first piece about it then. I have been through all of my papers now, and though it seems I have saved everything, I couldn’t find that article. It was for The Guardian, a long defunct broadsheet whose motto was “an independent Marxist-Leninist newsweekly.” I had started working there as a volunteer typesetter and found my first journalism mentors amongst the professional staff there. I wrote a number of AIDS pieces after that for them and for the Gay Community News, but I confess that the reality of the pandemic did not strike me until the early summer of 1983, when I saw people with AIDS for the first time. It was a terrifying and heartbreaking sight.