Activist and author Cleve Jones (www.clevejones.com) has rubbed shoulders with numerous important people including Harvey Milk, Nelson Mandela, George Clooney, President Obama, and many more. He has also been present at so many monumental, historic events like Milk’s big wins and the dramatic unveiling of the NAMES Project Memorial AIDS Quilt on Washington D.C.’s Mall during the 1987 March for LGBT Rights, that screenwriter Dustin Lance Black’s moth- er called him, “the gay Forrest Gump.”

“I didn’t quite know how to take that,” the lifelong activist admits, amused, “but I just happened to have been there, or placed myself, or was dragged in, during these monumental moments and situations.”

Portrayed by actor Emile Hirsch in the Harvey Milk biopic, MILK, and Guy Pearce in the 2017 ABC miniseries about the modern LGBT rights movement, When We Rise, Jones was a protégé of the groundbreaking, openly gay San Francisco politician, and later became custodian of his famed bullhorn. Jones co-founded the San Francisco AIDS Foundation (www.sfaf.org) in 1982, and three years later conceived the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt (www.aidsquilt.org), which maintains an online library of panels and traveling displays around the world.

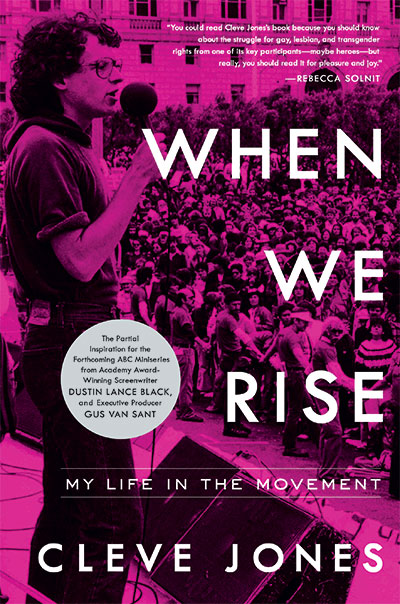

In November 2016, Jones released a memoir, When We Rise, which served as partial inspiration for the miniseries of the same name. The latter’s scripts were written by MILK’s Oscar-winning screenwriter, Dustin Lance Black, and directed by Gus Van Sant, Dee Rees, Thomas Schlamme, and Black.

Jones’ book, a colorful, episodic memoir, represents a breezy, frankly told trip through a life of profound ups and downs, featuring run-ins and encounters with names of historical, political, queer, and pop culture importance. Born in 1954, he revisits the difficulties and perils of being homosexual when it was considered a pitiable mental illness at best, criminal and life destroying at worst, to a joyful era of liberated, plentiful gay sex during the 1970s.

Cleve Jones in Amsterdam 1975

Jones also recounts his youthful travels around the world, often with little money in his pocket, and romantic/lustful trysts; the horrors the AIDS crisis later wrought; being diagnosed with HIV at age 31 and the ramifications of revealing his status publicly in a 60 Minutes episode; living with the virus and illnesses prior to effective treatments and, of course, after the protease inhibitor break-through; the NAMES Project’s creation; adventures in Hollywood during the making of MILK (a priceless anecdote involving Sean Penn alone makes this book worth every penny) and its resulting accolades and Oscars glamour; struggling to preserve San Francisco’s LGBT culture and history in the face of today’s soulless, crushing tech sector-driven real estate boom; and his passionate work for hotel and hospitality employees’ rights and benefits through the US/Canadian labor union UNITE Here! (www.unitehere.org).

During one memorable passage, Jones meets Paris Hilton, who “asked me what I did for work. I told her I helped organize underpaid workers in hotels, like those owned by her family. “That’s so cool,” she said. “Workers are hot.”

When We Rise is a compelling, engrossing read, by turns saucy, surprising, tragic, terrifying, funny, dishy, raw, hopeful, and inspiring, and easily could represent the first of many volumes. Jones admits that the experiences and anecdotes he didn’t share in its pages are multitudinous, from those that were simply too painful to recount at present, such as his mother’s death a couple of years ago, to encounters with world leaders.

“I just realized that I completely left out my trip to South Africa in 2000, when I met Nelson Mandela,” he shares. “I was help- ing out in the townships, and by pure luck he was speaking in the hotel I was staying in, and I got to talk with him and tell him the importance of making anti-retroviral medications available. It was quite a moment to meet one of the greatest heroes of our time.”

His meeting with President George H.W. Bush, hardly a hero to the LGBT community and AIDS activists, also didn’t make the cut, but Jones admits that, “I have a picture of us shaking hands hanging over my toilet in the bathroom!” he laughs, “I was in D.C. for a conference about HIV and we spoke, and the White House sent me a very nice framed photo afterward. I showed it to my grandmother, who despised Republicans. I said, ‘I don’t really know what to do with this picture. I don’t think I can just throw it away.’ She replied, ‘Hang it over the toilet!’ She was a very wise lady.”

Born in Indiana and raised in Arizona by a religious Quaker family, Jones first engaged with fellow queers and politics as a youth through small, discreet LGBT organizations and groups. He was energized by these experiences, and later drawn to the electric gay mecca of San Francisco, where hundreds arrived by bus daily to savor liberation in the lively Castro district. It was here that Jones met Harvey Milk (an early encounter is depicted in the movie MILK) and found a calling.

Meanwhile, Jones’ youthful travels, largely though Europe and Canada, also exposed him to numerous ways of life and activism, both in the streets and while hold- ing menial jobs. At Munich’s five-star Hotel Bayerischerhof, Jones toiled in a literally basement-level position alongside darker- skinned, lower-caste foreigners, and enjoyed—or rather, loathed—the same “outsider” status. This helped plant seeds for his later work empowering hospitality workers through UNITE Here!

“I have a program with them called ‘Sleep With The Right People,’ which is to get gay travelers and event planners to use hotels that have union contracts and respect their workers,” Jones says. “We have a fair hotel guide at www.fairhotel.org.”

At Harvey Milk’s side during his biggest successes and wins, Jones sometimes wield- ed the bullhorn a number of Jones’ speeches over the years are included word-for-word in When We Rise) and became its custodian following Milk’s assassination at the hands of unstable former city council member Dan White. The bullhorn, used in MILK and the When We Rise miniseries, currently resides at the Castro’s GLBT History Museum.

“That bullhorn gets around…still!” Jones laughs, adding that it had almost been stolen at least once or twice.

Recognized for his efforts and effective- ness alongside Milk, Jones found himself courted by other Californian politicians, including Milk’s former rival, Assemblyman Art Agnos, who approached him with an offer to work in the Sacramento legislature as part of an elite consultant group for the powerful Speaker Leo T. McCarthy.

When AIDS hit, Jones quickly turned his attentions to the mysterious, deadly crisis, forming the San Francisco AIDS Foundation with Dr. Marcus Conant, Frank Jacobson, and Richard Keller. In 1985, he conceived the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt as a therapeutic emotional vehicle for survivors and families of those felled by the modern plague, and as an accessible, visible way to raise mainstream consciousness while at it.

However, as recounted in When We Rise, a number of fellow activists, especially members of ACT-UP New York, were hostile to the AIDS Memorial Quilt, including Larry Kramer, who suggested it be burned.

“They called it the ‘Death Tarp,’” Jones recalls. “Part of that was a reflection of the differences in the two cities’ reactions to the epidemic. San Francisco didn’t have to deal with nearly as much hostility from the city government like in New York. It was a much harsher reality, so they were suspicious of the quilt and saw it as ‘West Coast touchy- feely bullshit.’ One of them said, ‘you’re not going to end the epidemic by making quilts.’ Nobody said we were, but the quilt had some very specific purposes, which it accomplished, and over time those critics eventually came around to understand it has power to mobilize and organize people and humanize the epidemic.”

Jones himself struggled with years of ill- ness wrought by the virus before effective treatments emerged, and spent time living in Russian River, where a community of HIV-positive people existed, before return- ing to his current home of San Francisco’s Castro district.

“The Russian River isn’t as gay as it used to be, but it’s absolutely beautiful and almost physically unchanged since the 1970s,” he relays. “Actually, that’s my retirement plan. I’m going to hang on here in the Castro as long as I can, but I would like to retire somewhere along the Russian River. I think it’s just the most beautiful part of the country, the scene is still kind of hippy, and every time I visit I run into old friends.”

When We Rise is actually Jones’ second book. The first, 2001’s Stitching A Revolution: The Making of an Activist, was largely co-authored with Jeff Dawson, his neighbor at the time. While it recounted some of Jones’ life and accomplishments, he felt it lacked his own voice, episodes from his youth and the time’s culture, and, most of all, sex, which he was finally able to do on his own with When We Rise.

Jones’ speaking and political engagements have taken him to destinations around the world, and some of those invitations have pleasantly surprised him. “One of the most moving was being invited to go to church with Miss Rosa Parks in Detroit,” he recalls. “Also I visited Indian reservations in the Dakotas and Alaska, and found it extremely moving. I’ve been to the Oscars, and I get to hang out with a lot of celebrities if you will, but that’s really not what I am. At the end of the day, you’re probably going to find me at the local dive bar I’ve been going to for 40 years drinking whiskey with the bartenders.”

At home in San Francisco, Jones keeps busy these days with the Harvey Milk LGBT Democratic Club (www.milkclub.org), Unite HERE!, with the SF AIDS Foundation advocating for wider use of, and affordable access to PrEP and the eradication of HIV stigma, and address- ing the San Francisco housing crisis.

Driven by landlords turning units into highly profitable Airbnb rentals, highly paid tech sec- tor employees continuously shattering real estate ceilings, and shiny developments like the infamous Millennium Tower (“Armistead Maupin called it ‘The Leaning Tower of Shadenfreude,’” he laughs), beloved San Francisco institutions both LGBT and straight alike are being forced to shutter, and longtime residents scattered to the fringes of the Bay Area and even beyond.

“The situation here is just appalling,” Jones laments, “and beyond a crisis. We really have no housing left for working-class people, for poor people. There’s no place to live for teachers or first responders, so when the inevitable big earthquake comes, our first responders won’t even be here. Basically, the entire city has been zoned a hotel which means you no longer know your neighbors, or have neighbors who share your concerns about neighborhood issues. Short-term rentals in a small amount can be very good, but what we’re seeing here, in Santa Cruz, and many other places is they really are destroying neighborhoods.

“In the Castro we’re also seeing the neighborhood becoming less gay with every month,” he continues. “There’s not a single lesbian bar left in this town, and maybe a third as many gay bars and clubs as in the 70s. There are serious consequences in that. There’s a tendency to trivialize the conversation, but if we lose the gayborhoods we lose that cultural vitality, we lose political power, and we lose the ability to provide specialized social services for our most vulnerable populations like seniors, HIV survivors, transgender people, and our youth. I’m real concerned and it’s also very frightening for me because I’m a renter, and I feel like I have a big target painted on my back.”

The Castro is, indeed, Jones’ place of call- ing, and since the 70s he’s been a fixture at dive bar The Mix. Asked where he would take first time Castro visitors, he proffers Catch restaurant, “which is in the building that was the last location of Milk’s Castro Camera and was the AIDS Quilt workshop for many years, and they honor the history of the building. There’s always a section of the quilt on display, photos of what the building used to look like, of Harvey. And it’s good seafood and the staff are very sweet.”

Where else? “The Twin Peaks Tavern, the first gay bar that had plate-glass windows and it’s kind of a haven for the older set. When I was young and impertinent, we had all sorts of rude names for the bar, which now I like. I’d take people to see where the original camera store was, which is now the Human Rights Campaign office, to the GLBT History Museum, and walk them around and show them the various names inscribed on the sidewalks.”

Fortunately, anyone can have a personal, Jones-led tour these days, thanks to the GPS-based app Detour.com, for which he recorded an audio tour. “It’s the coolest ever,” he enthuses, “and it knows where you are. If you stop, it’ll wait. A woman who used to be with NPR produced it. It has me talking and telling stories, but also archival audio, and it’s just so great.”