Berlin is a testament to the possibility of moving forward and learning from loss. A potent reminder that identity and opinions need not remain fixed; that open-mindedness and open-heartedness make good traveling companions.

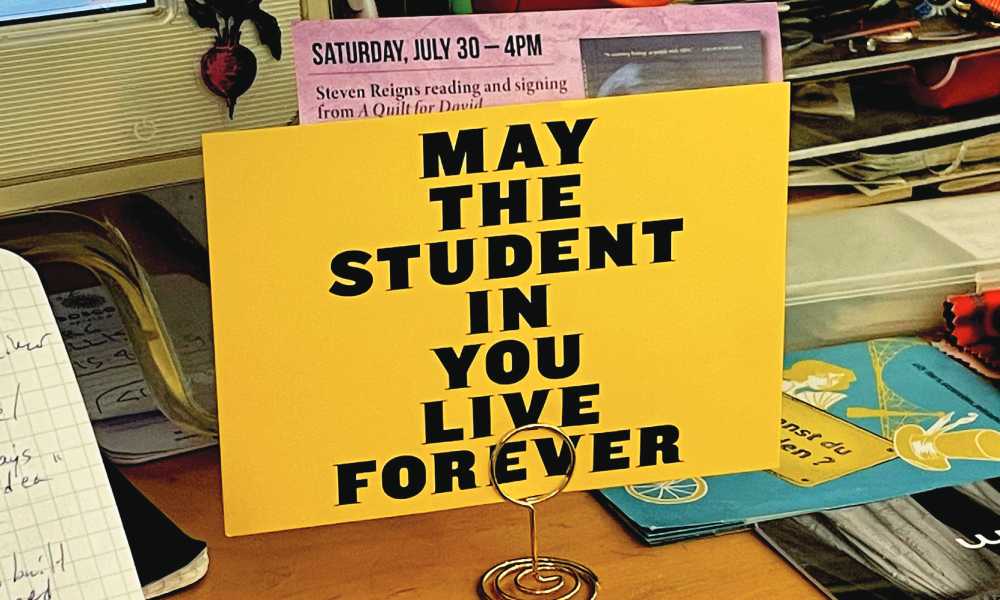

A souvenir of my first trip to Germany has held pride of place on my writing desk since I returned from a couple weeks there this past spring. It’s a simple postcard, bright yellow stock with black all-cap text that reads: May The Student In You Live Forever.

It welcomed me to my hotel room in Berlin when I checked in after a long day of flying from San Francisco with a brief, blurry layover in Munich. The sentiment was immediately appealing, but as jet-lag would have it, the card also brought a not-quite-coherent jumble of questions to mind: How much can a visitor experience in a fleeting week’s visit to a city? Am I the right guy for Berlin’s notorious gay nightlife? Isn’t that yellow color reminiscent of the fabric stars Jews were forced to wear by the Nazis during WWII? Was someone getting a haircut in the the lobby just now?

Startled awake by my room phone about two hours later, I answered with a disoriented “Huhoh?” “This is the front desk, there’s a Mister Holger here to see you.” “OK, Be right down!” I slapped cold water on my face, sprinted to the elevator and pushed L, for my trip’s first lessons.

It turned out that, yes, someone had been getting a haircut in the lobby. Buzzes and trims are among the surprising array of services offered by my home base for the next few days: The Student Hotel. (That postcard, in addition to inspiring me, was a successful sticky bit of brand marketing).

Student Hotel Lounge (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

One of the first in a new concept chain now operating in a dozen European cities, the 475-room Student, Berlin, offers modestly priced tourist accommodations as well as housing for international enrollees in semester abroad programs at local universities.

Dedicated rooms for travelers are separated from student quarters (which include communal kitchens); but sprawling indoor and outdoor lounges, quiet work/study rooms, free shared bicycles, a generously sized gym and lobby pop-up shops are open to all.

There’s no tatty-round-the-edges hostel vibe here, but the whole place does buzz with youthful energy, and students willing to share tips on their own recent urban discoveries. I met friendly kids from France, Spain, Holland and Brazil, all happy to engage in conversation with a middle aged American stranger to whatever extent their English skills would allow. A stay at the Student fits Berlin’s gestalt. This is a city that is always reinventing itself, perpetually in the throes of its latest youth.

EAST MEETS WEST

In the lobby, I met Holger Linde-Margalit, a native Berliner who leads food and LGBTQ-themed tours of his city. Now 53, he was a college student during of one of the city’s most dramatic reinventions. As we stepped out into a balmy spring evening, he recalled joyful chaos in the streets on November 9, 1989 when, after 28 years as an island of democracy surrounded by Soviet controlled East Germany, the Berlin Wall came down.

Postard (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

Berlin is a testament to the possibility of moving forward and learning from loss. It’s a potent reminder that identity, and opinions, need not remain fixed; that open mindedness and open heartedness make good traveling companions.

“It was wonderful. Crazy.” Holger recalled of the clamor on both sides of the quick-dissolving border. “Everyone was out celebrating.”

The Student’s location in contemporary Berlin’s central district (called Mitte) would have fallen within East Berlin, less than a mile from the walled border. Just to its south, the Kreuzberg kiez (an affectionate term Berliners for their neighborhoods) has long been home to some of the city’s best people watching.

“This was the end of the world in the 80s and 90s,” explained Holger as we walked through the borough, “It was awesome.” Situated at the easternmost edge of West Berlin, the borough was a poor area with a large Turkish immigrant population. But artists, gays and iconoclasts of all sorts began moving here for the cheap rents and sense of frontier freedom, building community and, eventually, establishing businesses. But even today, compared to what’s thought of as gentrification in most cities, the bar and gallery-lined Oranienstrasse and its environs still have a jostling, multicultural, rough and tumble feel.

They also still have plenty of Turkish food. Among the stops on my Fork & Walk tour with Holger was Doyum, an otherwise modest looking joint considerably spruced up by walls of intricately patterned blue tile. The cumin-scented smoke wafting from the grill had my mouth watering and the kusbasi pide, an oval flatbread covered in fragrant, oilslick lamb strip and ezme, a vibrant spread of fine chopped tomatoes, onions, walnuts, and red pepper purée didn’t disappoint. Ayran, a traditional drink made with tangy natural yogurt, water and salt was a surprisingly comforting accompaniment.

Given the city’s proliferation of kebab stands, it could reasonably be argued that Turkish is Berlin’s signature cuisine. But Ach nein!, an army of Omas would surely protest, so to keep the grannies at bay, Holger took me to a sleek little bistro called Klinke, where you can actually have a meal of traditionally heavy German cuisine and still have the energy to go dancing afterwards. Call it Teutonic tapas: delicate, elevated three-bite versions of classics like cheese spaetzle topped with crispy onions, dumplings and blood sausage, golden potato croquettes, or a few wee meatballs. Wash it down with a nice glass of Gewurtztraminer and you’re good to go, pants still buttoned.

For a post-prandial promenade, stroll east for about 20 minutes to the Spree River. Just across the bridge is the East Side Gallery, an almost milelong section of the Berlin Wall left standing and transformed into a fantastic gallery of street art. It features over 100 murals by artists from 21 countries, the most famous of which is “My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love,” which satirically depicts a juicy kiss between Leonid Brezhnev and Erich Honecker, former leaders of the U.S.S.R. and East Germany (Brezhnev died in 1982; Honecker fled to Chile after the fall of the Wall but was later brought back to Germany to stand trial for human rights abuses).

ELEPHANTS IN THE ROOM

As I woke up on my first full day in in the city, that bright yellow postcard caught my eye once again, and I felt its words goading me into scholarly seriousness: of all the places I’ve had the good fortune to visit in this world, Berlin felt the most freighted with educational obligation. As a gay Jewish man, there was a part of me that, frankly, felt strange about vacationing in the capital of a country where members of my extended genetic and chosen families had been systematically persecuted in relatively recent times. Was this a place I could let myself enjoy, or did it demand sober revisiting of history lessons?

Both, perhaps, but there was no way to ignore the latter. Berlin, to its credit, while constantly evolving, is not in the business of forgetting. There are markers and memorials to victims of the Holocaust throughout the city and they’re well worth visiting over the course of a stay.

Architectural Detail Palast Theater (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

The best known is a field of almost 3,000 irregularly arranged concrete slabs of varying heights, bluntly named Memorial for the Murdered Jews of Europe. While the design, by architect Peter Eisenman has been criticized by some as too cool and abstract, I found that walking within its vast gray disorder generated a compelling mixture of reflection and unease. The site’s enormous size and disruptive effect in the center of the city force regular reckoning and wrestling with the history it represents.

I leavened my mood by returning to the Kreuzberg neighborhood to visit a more life-affirming counterpart to this memorial, the Jewish Museum Berlin. One of the most visited museums in all of Germany, in part because of its stunning titanium-clad lightning strike design by American architect Daniel Liebeskind. It pays tribute to the cultural, intellectual and spiritual contribution of Jews in Germany both before and beyond the Holocaust.

Just a few blocks away from the Jewish Holocaust memorial, on the grounds of 520-acre Tiergarten Park, known as the city’s “green lung,” is the Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted Under Nazism. Echoing the larger memorial, it consists of a huge, irregular black concrete block, but a small window reveals an interior chamber where a brief film of same-sex kissing plays in a loop, ingeniously defying death in its transmission of unending passion.

Nearby in the park, a circular reflecting pool memorializes the Sinti and Roma (pejoratively referred to as ‘gypsy’) victims of the Holocaust, a single flower at its center is replaced each day.

Two Holocaust memorials resonated more strongly for me than those paying tribute to specific populations of victims. At the Bebelplatz, a public square where thousands of confiscated books deemed representative of “decadence and moral decay” (among them works by Einstein, Marx, Freud and Thomas Mann) were burned at an enormous Nazi rally in 1933, is Israeli artist Micha Ullman’s permanent installation, The Sunken Library.

East Berlin TV Tower (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

As you walk across what appears to be an empty cobblestone courtyard, you arrive at a transparent glass plate; look down and you’ll see a spare white underground room lined with empty bookshelves, enough space for the 20,000 volumes that were incinerated. Visit after dark, when soft light rises from the hollow, persistent illumination instead of flames lit by ignorance and intolerance.

Most moving of all was the Stolpersteine, or stumbling stones, a unique memorial scattered throughout Berlin and beyond. Since 1992, nearly 80,000 of these 4”x 4” metal blocks have been embedded in sidewalks just outside the last homes where people lived before they fled or were “relocated” due to Nazi persecution.

Their upper surfaces, each engraved with the name of a single person, lie flush with the pavement. Relatively inconspicuous individually, the stones’ aggregate power is immense. As a pedestrian unexpectedly ‘stumbles’ across them from time to time, they find themself momentarily engaged with an ever-present past. The stolpersteine helped me keep my balance through a week of walking in Berlin: “Never forget,” they nudged. “But as long as you carry the lessons of memory, its ok to keep moving along.”

CURIOUS CUISINE

As anyone who’s ever sat shiva can tell you, mourning can work up a healthy appetite. So one evening, after thirty minutes’ meditative journaling at the gay memorial, I treated myself to a high-end meal with a queer Berlin spin. Located in the edgy, chic Neukolln neighborhood, the restaurant Coda has two Michelin-stars and a set menu of seven courses, every one of them a dessert.

Candied Lettuce at Coda (Photo by Jim Gladstone)

In the hands of culinary impresario René Frank, ‘dessert’ is a nonbinary term, without fixed ties to the savory or the sweet; it signifies only that each dish is made using techniques he’s developed across kitchens in Spain, France, Japan and Switzerland, winning four global “Pastry Chef of the Year” awards.

Using no refined sugar whatsoever, Frank and the small team in his hushed, laboratory-like open kitchen coax muted natural sweetness out of a wide range of largely vegetarian ingredients, then combine them in visually elegant and texturally exciting combinations. Candied lettuce with pickles? Beetroot gummy bears? A tiny waffle with raclette cheese and powdered kimchi? Yes, yes, and yes. It’s as if Willy Wonka bonked the Jolly Green Giant.