These movie museums are your global passport to the world of cinema magic, dreams and achievements; past, present and future.

On September 16, 1890, Louis Le Prince, a French engineer based in Leeds, England, boarded a train in Dijon for Paris. Visiting family in France at the time, he was U.S.-bound for a date with destiny, straight out of the movies.

Two years earlier, in October 1888, Le Prince had verifiably made the world’s first motion picture. Using a single-lens camera of his invention, Le Prince filmed family members in a suburban garden, and a traffic crossing at Leeds Bridge. Invited to publicly screen his shorts in New York City, he was headed for certain glory. After his train arrived in Paris, however, Le Prince and his luggage vanished without a trace. The discovery in 2004 of an 1890 police photo showing a drowned man resembling Le Prince being pulled from the Seine revived long-held allegations of suicide or foul play.

Whatever his fate, Le Prince became the forgotten father of film, and poster figure for the many beguiling secrets behind the veil of movies. For cinephiles and fans of art, culture, fashion, history, science, sound, and technology, movie museums are center stage for fascination and imagination. Linked by history and their own compelling origin stories, here are the top museums around the globe featuring the magic of the movies.

Just west of Leeds, Bradford, birthplace of pop art legend David Hockney, was recognized as the world’s first UNESCO City of Film in 2009. With a rich filmmaking heritage, this scenic West Yorkshire city is home of The National Science and Media Museum (Tel.: +44-330-058-0058. www.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk).

The free-admission institution’s wide-ranging collection includes Le Prince’s mahogany-box camera and frames of his footage. The three-screen Pictureville Cinema includes England’s first IMAX theater.

In the Victorian era’s blur of motion picture invention, “who shot first” is a contentious and complex question. Principal cast members include English photographer Eadweard Muybridge and his 1879 Zoopraxiscope projector, which he showed to Thomas Edison in 1888. Edison’s British employee William Kennedy-Laurie Dickson subsequently devised the revolutionary Kinetograph motion picture camera and Kinetoscope loop projector.

Introduced in New York City and rolled out internationally in 1894, Kinetoscope parlors were the first commercial movie houses. That year, Dickson went solo with his Mutoscope, while Charles Jenkins and Thomas Armat created the Phantoscope. In April 1896, after acquiring a modified version of the latter and marketing it as his Vitascope, Edison screened shorts to what he claimed was the world’s first paying audience in New York City.

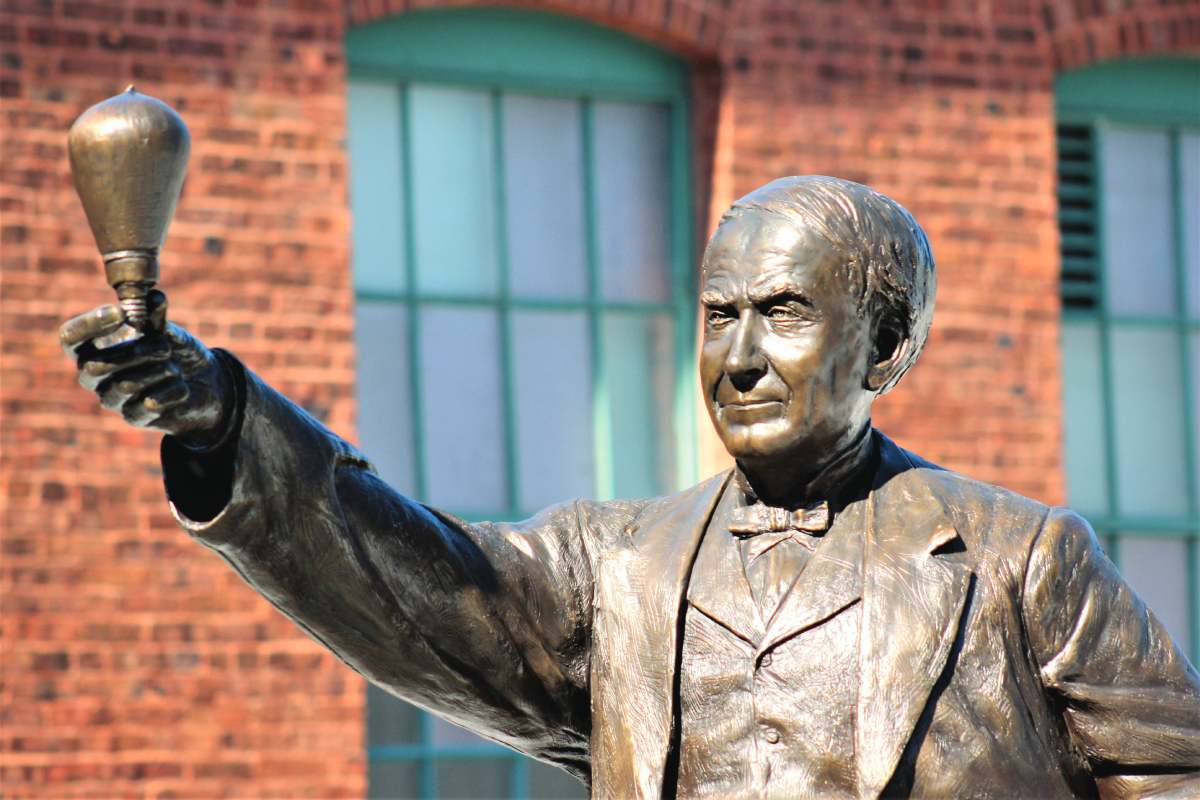

Thomas Edison statue at Thomas Edison National Historical Park (CREDIT Jeff Heilman)

Chronologies aside, indisputable are the wonders that originated from Edison’s former laboratory and factory complex in New Jersey, preserved today as Thomas Edison National Historical Park (211 Main Street, West Orange, NJ. Tel: 973-736-0550. www.nps.gov/edis). Exhibits include his pioneering projectors and a reproduction of his Black Maria (1893), the world’s first film studio. Visitors can also tour Glenmont, Edison’s nearby 29-room Queen Anne-style mansion-estate.

Returning to 1894, the pioneer plot was thickening in France. After viewing Edison’s Kinetoscope in Paris in 1894, Lyon-based photographer Antoine Lumière (fittingly, “light” in French) tasked his sons Auguste and Louis with improving the technology. The result was the Cinématographe, a combination camera, projector, and film printer, which the brothers used to film La Sortie des ouvriers de l’usine Lumière (Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory) in early 1895. Premiering the film and nine shorts to 33 paying audience members in Paris that December, they have their own claim to the birth of cinema.

The Lumière family also found fame and fortune with their revolutionary dry plate developing process. Today, their ornate former 21- room mansion is Institut Lumière (25 rue du Premier Film, Lyon. Tel: 04-7878-1895. www.institut-lumiere.org). Exhibits include the Cinématographe, and other inventions such as the 360-degree Photorama camera. Housed in the former Lumière factory, the Hangar du PremierFilm theatre screens diverse year-round programming such as recent Stanley Kubrick and Marcello Mastroianni retrospectives.

Celebrating classic and contemporary cinema each October, Lyon’s Lumière Festival (www.festival-lumiere.org) rivals Cannes, celebrities included. The city’s gastronomic glory is another reason to go.

La Cinémathèque française (CREDIT Stéphane Dabrowski)

With so many wonderful venues dedicated to filmmaking, past, present and future, these movie museums are your global passport to the world of cinema magic, dreams and achievements.

France is also home to Cinémathèque Francaise (51 Rue de Bercy, Paris. Tel: +33-1-7119-3333. www.cinematheque.fr). Founded by Henri Langlois, who secreted away a trove of movies and related materials ahead of the Nazi invasion, this 1936 Parisian institution preserves one of the world’s largest film archives. Once championed by François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, the Museum today resides in a Frank Gehry building at Parc de Bercy. “Méliès: the Magic of Cinema” is a new permanent installation devoted to Georges Méliès, the prolific French filmmaker whose pioneering special effects are immortalized in works such as A Trip to the Moon (1902). With public and private resource libraries and daily screenings, it’s a haven for cinephiles and researchers.

Musée Méliès (©La Cinémathèque française 2)

As cinema rapidly evolved heading into the 20th century, film studios and equipment, as well as production and distribution companies flourished in Europe and the U.S. By 1912, some 15 film companies were operating in Hollywood. America’s original film capital, however, was Fort Lee in New Jersey, across the Hudson River from New York City.

In 1905, pioneers such as D.W. Griffith began filming in the borough. By WWI, up to 17 studios operated in Fort Lee. Among them were future titans Universal (originally Champion, 1910); Fox, founded in 1915 by Hungarian immigrant William Fox; and Goldwyn, which became part of MGM in 1924.

Divided by the George Washington Bridge roadway today, the campus offered a natural backlot. Rural Main Street doubled for western towns, while the soaring rock walls of the Palisades were ready made for action flicks. Early classics included Robin Hood (1912) and the Perils of Pauline series, from which the industry term “cliffhanger” was born. Below, the shoreline stood in for seaside and water features. Threaded with hiking trails, the Palisades’ forested clifftop is a de facto heritage site. Following WWI, the studio migration to sunnier and more cost-effective Hollywood was on.

Four Star-Studded Stays in Los Angeles

Tropicana Pool (COURTESY Hollywood Roosevelt)

I love Terry O’Neill’s 1977 photo of Faye Dunaway breakfasting poolside at the Beverly Hills Hotel early in he morning after winning Best Actress for Network. Her Oscar on the table and newspapers at her feet, Dunaway’s far away gaze is a mesmerizing portrait of post climactic decompression. Need your own A-list unwind? Here are four L.A. hotels that provide all their guests the star treatment.

Built by and for Hollywood’s elite in 1927, Hollywood Roosevelt (7000 Hollywood Boulevard. Tel: 323-

856-1970. www.thehollywoodroosevelt.com) is L.A.’s oldest continuously operating hotel. Time-capsule venues inside this 300-room Spanish Colonial Revival treasure include the Blossom Ballroom, which hosted the inaugural Academy Awards in 1929. Overlooking the famed Tropicana Pool with its multi-million-dollar David Hockney mural, Room 229 was Marilyn Monroe’s pre-fame home for two years. Clark Gable and Carole Lombard once called the Penthouse Suite and its panoramic rooftop patio home. Montgomery Clift stayed in Room 928 while filming From Here to Eternity. Shirley Temple practiced tap-dancing with Bill “Bojangles” Robinson on the Spanish-tiled steps near the lobby. With a view of the legendary 1927 TCL Chinese Theater across Hollywood Boulevard, my vintage 8th-floor room was an appointment with history, complete with a wooden four-poster bed. Guest hideaways include The Spare Room, a prohibition era-style cocktail lounge, and private Writer’s Room.

Loews Hollywood Hotel (1755 N. Highland Avenue. Tel: 323-856-1200. www.loewshotels.com/Hollywood-Hotel) embodies the essence of Hollywood today. Located adjacent to the Dolby Theatre (www.dolbytheatre.com), home of the Academy Awards and other major movie events, the 628-room AAA Four Diamond property hosts press coverage of the Oscar winners. With a widescreen view of the Hollywood Hills, my spacious 16th-floor room invited dreams of stardom. Connected to the Hollywood & Highland Center retail and entertainment complex, where the top-level Ray Dolby Ballroom hosts the official Governor’s Ball after-party, the hotel buzzes with celebrities on Oscar weekend. Guided Dolby Theatre tours bring the Oscar magic alive. The hotel’s Panorama Suite is an A-list haven with history. In 1970, when the building opened as the Holiday Inn-Hollywood, the space was Oscar’s, a revolving rooftop restaurant and nightclub with two stages. Today, it is a fabulous penthouse offering 280-degree Hollywood views.

In April 2021, Pendry Hotels & Resorts, Montage International’s new luxury flag, made its L.A. debut with Pendry West Hollywood (8430 Sunset Boulevard. Tel.: 310-928-9000. www.pendry.com/west-hollywood). Built on the former site of acting legend John Barrymore’s home and most recently, the House of Blues, the block-long contemporary glass shell houses a 149-room wonderland with an enchanting checkerboard arrival piazza. Curated artworks include “Sunset Jewel” at the porte cochère, a 23-foot-talls golden tree sculpture with mother of pearl leaves. In the lobby, L.A.-based artist Anthony James’ “Icosahedron” is a trippy 20-sided steel-and-glass portal of infinite equilateral triangles. Check in includes a welcome beverage and complimentary spike at Bar Pendry. Panoramically overlooking L.A., my Skyline King Room was pure comfort. Wolfgang Puck runs the culinary program, with son Byron Lazaroff-Puck serving as General Manager of Merois, a gorgeous Asian-inspired bistro adjacent to the rooftop pool. There’s also casual dining at street-level European style café Ospero, plus 100-seat live music club, spa and fitness club, screening room, and bowling alley.

Opened in 1966 on a former 20th Century Fox backlot, World Trade Center architect Minoru Yamasaki’s curvaceous 750-room Century Plaza hotel was the center of the L.A universe for events and rock royalty. The Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” commanded the 10th annual Grammys here in 1968. The following year, the hotel hosted the first-ever Presidential State Dinner outside the White House in honor of Apollo 11. Sonny & Cher performed nightly and recorded their first live album here in 1971, while Elton John played privately for MCA executives in 1978. Following a fiveyear, $2.5 billion makeover unveiled in September 2021, “The World’s Most Beautiful Hotel” is back as Fairmont Century Plaza (2025 Avenue of the Stars. Tel: 310-424-3030. www.fairmontcenturyplaza.com). Spanish artist Jaume Plensa’s 23-foot-tall mesh sculpture “Laura” floatingly fronts the landmarked exterior of 400 balconied guest rooms and suites. The chic lobby invites sipping music-inspired “Live at Century Plaza” cocktails amid water features and living walls. Lumière, after the cinema pioneers, is an evocative French-inspired brasserie offering cozy indoor and outdoor dining. Revolutionary anti-aging and other treatments make the Fairmont Spa Century Plaza a veritable fountain of youth. With the hotel’s underground connection to Creative Artists Agency (CAA) across the street, the Spa is A-list ready