Your first journalism jobs in New York were for gay publications, and your articles were about the AIDS epidemic. Was it frustrating to you that mainstream publications were either publishing little or nothing about the epidemic, and did you have a desire to write for them because of that?

I didn’t expect anything good from mainstream media back then, bent as they were on damning us publicly. Remember it was the heyday of the “Alternative Presses.” When periodicals like the Village Voice and The Nation ignored the pandemic. That was by far more frustrating. My motivation in covering AIDS, at least from 1983 onward, was to just be doing SOMETHING. By then my friends had all signed up for the war in one way or another. I was writing infrequently, making my money as a typesetter and going to grad school while they were visiting AIDS patients in hospitals or volunteering for GMHC or other AIDS organizations. In 1984 I quit The New School and took a full time journalism job at the New York Native to cover AIDS. It was what I could do, and my effort at being useful.

You were fired from the New York Post for being gay. Tell us about that experience.

A friend and mentor at the Post, Joe Nicholson, one of 2 out gay mainstream journalists in the country, invited me to come onboard there. He had managed to come out by securing union protections. He helped me create a meaningless resume and got my foot in the door, but long before I earned enough time on staff to become a union member, my truth was routed out and I was canned; ostensibly for lying on my resume about not having worked in journalism previously. I would like to tell you that I made a stink about the firing, shouting and shaking my fist, but I didn’t. I walked out feeling ashamed and physically sick.

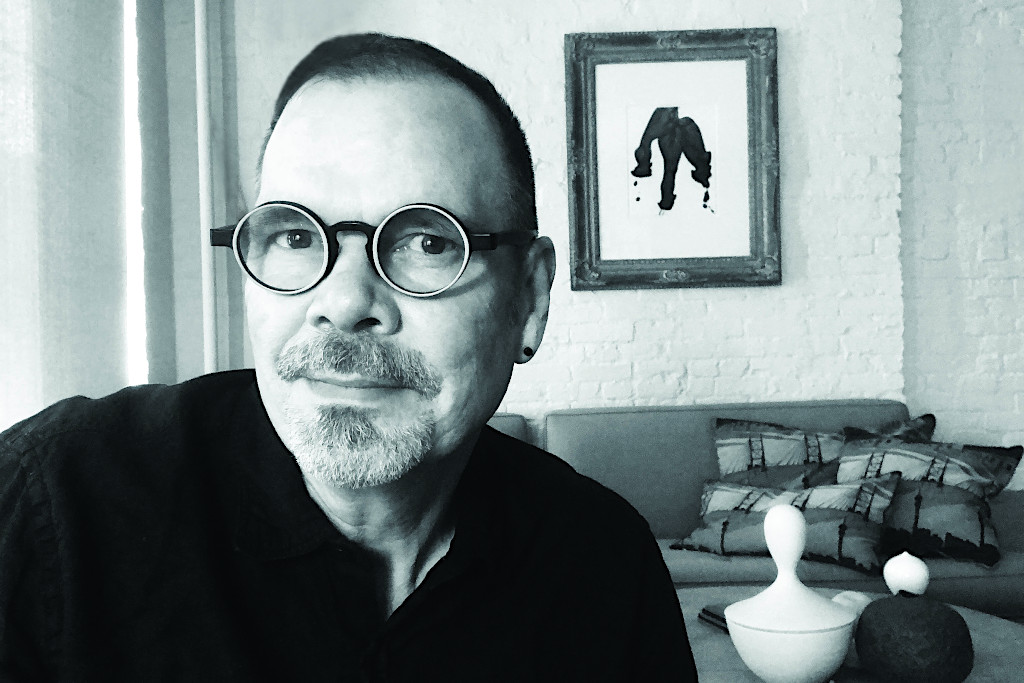

David at NYC Pride March in 1983

Photo: © Nelson Sullivan

You went from the trenches of working at a tough New York newspaper to the trenches of Central America, as a war correspondent. Even though they were geographically worlds apart, were there any similarities in the job?

I went into the war zone after the Post experience. I thought that if I was going to get the opportunity to tell the AIDS stories in mainstream outlets, I was going to have to prove myself in traditional ways. My Spanish was quite good as I had spent a year studying in Bogota, Colombia. And the “Contra Wars” were the biggest thing happening in global journalism at the time. So I went, with a press card provided by Religion News Service (another place that would respond to a meaningless resume). They were very good to me and taught me a lot and let me file stories for them for two years. I returned to Central America for Rolling Stone and others over the years, and the area has remained of great interest to me. Were there similarities? I have often said that New York and Central America were both fighting life-and-death wars, the difference being that my friends were not dying in Central America. So for me, even the most intense frontline war reporting I was doing was considerably easier to handle emotionally than what was happening on the streets in America.

Another interesting transition was you went from Central America to writing for women’s magazines such as Glamour, as the National Affairs Editor. Did you write in a different tone and way because you were writing for a female reader?

Interesting question! I broke into magazines with a spectacular story for Vanity Fair, a 10,000-word piece about an unsolved murder case in New York. This brought me to the attention of a lot of magazine editors. One of them was Betsy Carter, the editor-in-chief of New York Woman magazine, a spin-off from Esquire. She took me under her wing, published me, and promoted me to her contacts in women’s magazines. I was not already a reader of those magazines, but I was amazed at the depth of the work they were publishing. There was no “dumbing down.” They published some of the hardest-hitting journalism I had read. They allowed me to take on some very intense stories over the years, including on AIDS. I wrote (for Good Housekeeping) about the first woman in America to knowingly become pregnant despite being HIV positive, something she did after careful research and by liaising with scientists, evaluating published journal studies, and consulting with her husband and family. (The kid, Tyler, is now in his mid-twenties and HIV-negative.) I wrote (for Mirabella) about laws criminalizing sexual behavior of HIV-positive women, and (for Glamour) about the challenges people with HIV faced when effective medication was finally available and they were suddenly facing the possibility of an ordinary life. This led me to the position at Glamour, which I held for many years. I truly loved the work and admired the editors and writers there more than any place else I have worked. But simultaneously I wrote for The New York Times as an HIV/AIDS health reporter and for POZ magazine, among others, maintaining AIDS as my primary beat.

Why did you decide to make the film How to Survive a Plague before you wrote the book? Was the book a complement to the film and did you feel it would give it another dimension in an alternate media form or was there a different intent for the book to follow the film?

It wasn’t my decision, it was the market’s! I was shopping for a book proposal in 2009 when the market collapsed, and print went into a tailspin. I literally got no interest in the book, and at the time I was working as a contributing editor at New York magazine, where I was put on a shelf. So mostly to keep myself from death by boredom, I started playing with that old footage.

Welcome to Chechnya

Photo courtesy of HBO

Your latest film Welcome to Chechnya is a daring and harrowing expose of the persecution of the LGBTQ community in Chechnya. How and when did you first learn about the situation there and what prompted you to make the film?

I heard about the genocide there in early 2017, when the rest of the world did, but it wasn’t until reading Masha Gessen’s piece in The New Yorker that summer that I became aware of the work that ordinary queer activists were taking on to save lives. That’s the story that drew my attention, and that’s where I thought I might be able to make a difference, by lifting up their stories. I was literally blown away when I learned about the secret underground work they were doing, and the incredible personal risks they assumed. That this was happening in today’s world? In the 21st Century, and not in Nazi-occupied Europe? I was floored.

You literally put your life on the line when filming Welcome to Chechnya. Did you know the extent of danger involved before you decided to make the film?

I assumed it would be very dangerous, and I was certainly willing to take on risks if it could help. And unlike the Contra Wars, I felt very personally invested in this struggle. But it wasn’t until I made my first trip to Russia that I began to understand the stakes. I immediately hired outside security consultants to make sure I was not endangering the crew or the people we were trying to help. We built an intense operation, creating 25-page security protocols for each of the filming sessions, and even more security for safeguarding the footage. It was very important that the footage not fall into the wrong hands, exposing the identities of the people we were filming.

What was their reaction when the people in the film saw the outcome of the altered facial identities.

They were blown away, as I knew they would be. I learned that they were not at all confident that I would find a working solution, and they all had the right to veto any approach that failed to meet their high standards. I had promised that I would disguise them to “the highest standard,” which was that even their own mothers wouldn’t recognize them. Luckily, I got signoffs from them all. It was very fun to talk to them about watching scenes of their own lives, but with somebody else’s face. Maxim, one of the survivors, said it had an interesting psychological power, releasing him a bit from his own story of terror and torture, a kind of dissociation by VFX, I guess!

What are some of your upcoming projects?

I’m working with HBO on a documentary project about COVID science—kind of a How To Survive A Plague 2.

You May Also Enjoy

John Cameron Mitchell Re-Releases His Ground Breaking Film, SHORTBUS

John Cameron Mitchell Rereleases His Groundbreaking Film ‘Shortbus’